By Randy Skretvedt

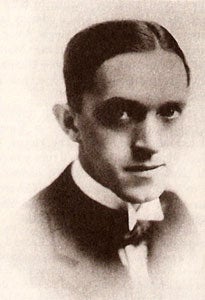

June 16 marks the 121st anniversary of the birth of Arthur Stanley Jefferson, better known as Stan Laurel. We remember him primarily for the relatively brief time—fourteen years—in which Laurel and Hardy made their best films for the Hal Roach Studios, from 1927 to 1940, but he toiled hard to create laughter for most of his life. He worked steadily for twenty years, learning his craft and refining his art, before the first “Laurel and Hardy” film flashed onto theater screens.

It seems that nobody ever called him Arthur, and there’s evidence that he didn’t much care for “Stanley,” either, preferring to be known only as “Stan.” For that matter, although his father was named Arthur Jefferson, he was always called “A.J.” Stan’s mother was properly named Margaret Metcalfe Jefferson, but she went by “Madge.”

By any names, the Jeffersons were a talented family. A.J. was a playwright, actor, director, producer and manager of several theaters in the north of England, and Madge was a popular actress. A.J. and Madge had married on March 19, 1884, and the next year their first son, George Gordon Jefferson, was born. Arthur Stanley was the next offspring, born June 16, 1890 at 3 Foundry Cottages in Ulverston, England, then part of the county of Lancashire. The small house in which Stan was born was the home of Madge’s parents, George and Sarah Metcalfe. Stan was often quite sickly as a child, so he remained at the Metcalfe home, largely being raised by his maternal grandmother, while A.J., Madge and Gordon were on tour.

Theatrical Debut

Being raised in a theatrical family, it should have surprised nobody that young Stan was obsessed with anything that had to do with putting on a show. He made his first appearance on stage at age seven, with a small part as a newsboy in one of his father’s plays, Lights of London. When Stan was nine, A.J. yielded to his pleas and converted the attic of the family’s new home (at 8 Dockwray Square in North Shields) into a miniature theater. As A.J. later wrote, it had “stage, proscenium, wings etc., and footlights (the latter being oil lamps with reflectors, safer than gas we thought), with seating capacity for about 20 to 30 people, in brief a replica of the average small theatre at that period.” Stan had had the theater for about a year, producing several plays co-starring neighborhood kids, when he put on a melodrama which featured the nearby butcher’s son, Harold, as a snarling villain. Stan and Harold enacted a “fight to the death,” grappling on the floor of the stage, during which Harold kicked over one of the paraffin oil lamps and caught the curtains on fire. Although the blaze was put out before too much damage was done, A.J. dismantled the theater soon after.

A.J. repeatedly told Stan that being an actor was full of hardships, that it was a far wiser course to pursue the management end of show business. None of this dissuaded Stan from wanting to perform. In 1905, the family moved to Glasgow, A.J. now running a larger theater, the Metropole. Here Stan saw and idolized the “boy comedians,” teenagers who told jokes and sang funny songs in the manner of the adult stars of Music Hall. Nipper Lane (later known as Lupino Lane), Laddie Glen, Wee Georgie Wood—Stan longed to join their ranks.

The act went over quite well, until Stan was taking his bows and spotted his father in the audience—which prompted him to run offstage in a panic...

Thus, in 1906, at the age of sixteen, Stan paid a half crown to a tunesmith for an original song, and cobbled together enough jokes for a suitable monologue. Without A.J. knowing it, Stan borrowed his dad’s new trousers, frock coat and silk hat, and auditioned for a spot as an “extra turn” on the stage of Glasgow’s Brittania Theatre, run by one of A.J.’s friends, Albert Pickard. By sheer coincidence A.J. happened to walk into the theater on the night of Stan’s planned debut and greet Pickard, to be met with the astonishing news that Stan would be on in five minutes. The act went over quite well, until Stan was taking his bows and spotted his father in the audience—which prompted him to run offstage in a panic, catching the precious frock coat on a steel hook and tearing it. A howl for the audience, but not so funny to A.J. When Stan finally got up the nerve to face his father in his office, A.J. said nothing for a long time. He finally broke the silence with, “Not bad, son, but where on earth did you get those gags? Have a whisky and soda?”

A.J. was resigned to his son’s aspirations, and found him a place with the company of Harold B. Levy and J.E. Cardwell, who specialized in putting on “pantomimes”—parodies of children’s stories—featuring young performers. In the production of Sleeping Beauty—not the usual story but instead a tale of toys that come to life—Stan played “Ebeneezer, Golliwog number two,” a large stuffed rag doll. The production began its tour on August 19, 1907 and ran through April 19, 1908.

Stan's First Tour

From that point on, “Stan Jefferson” toured the provinces in one show after another. The Gentleman Jockey took him through the summer of 1908, at which point Stan toured in a sketch called Home from the Honeymoon, written by A.J. Stan liked this one so much that he used it as the basis of two films with Oliver Hardy, Duck Soup (1927) and Another Fine Mess (1930). Another Levy and Cardwell show, The House That Jack Built, ran through April 1909, and that summer Stan toured in a show imported from the States called Alone in the World. Stan had two roles in this, one as a policeman named “Stoney Broke,” and another as a tramp fishing on a levee in the Deep South. To the end of his days, Stan remembered a scene where, as an offstage choir sang “Swanee River,” he turned to the audience and said, “Wal, I guess ‘n’ calculate I cain’t ketch no fish with that tarnation mob a-singin’. Gee whiz!” However mortified Stan may have been by this material, he got good reviews, one paper praising him thusly: “Mr. Stanley Jefferson is a first-rate comedian and dancer, and his eccentricities create roars of laughter.”

Those eccentricities were on display during the fall of 1909 in a solo act, “Stan Jefferson—He of the Funny Ways.” Back home in Glasgow and looking for another show, Stan went to see the pantomime of Mother Goose at the Grand Theater, produced by the illustrious impresario Fred Karno. Karno had essentially created the music-hall comedy sketch; most music-hall performers sang funny songs, but Karno’s comedians worked in pantomime. This was primarily to escape the license fees and censorship imposed by Lord Chamberlain’s office, which insisted upon reviewing the script of every play produced in Britain. Karno reasoned that if there was no dialogue, there need be no script, therefore no censorship problem and no license to be paid. What began as a financial consideration resulted in a new form of comedy. So popular were these sketches that troupes of his comedians—dubbed by the public as “Fred Karno’s Army”—were appearing in theaters all through England during the early years of the 20th century.

Backstage after seeing Mother Goose, Stan happened upon a “gentle-voiced little man” and expressed his wish to see Mr. Karno. “You’re seeing him now,” the man replied, and Stan asked for a job, noting his prior experience. Karno hired him on the spot—at two pounds a week—and told him to join the company of a sketch called Mumming Birds in Manchester. The set for Mumming Birds was a theater within a theater, on the stage of which a procession of truly hideous performers were abused in creative ways by an equally hideous audience. Stan appeared in three other Karno sketches—Skating, Jimmy the Fearless and The Wow-Wows—and then came to the United States for the first time in September, 1910 with a Karno touring company. The star comedian was Charlie Chaplin, whose specialty was playing an angry drunk in the Mumming Birds audience.

On the Road with Charlie Chaplin

Stan was Chaplin’s roommate and understudy, and while Chaplin was Stan’s friend he was also a hindrance to his becoming anything more than a supporting player. This, and the refusal of a raise in pay, prompted Stan and a fellow Karnoite, Arthur Dandoe, to return to England in the late summer of 1911. They worked up an act as gladiators, called it The Rum’uns from Rome, and dubbed themselves The Barto Brothers, to no great acclaim. In fact, to no acclaim whatsoever. The Brothers parted ways; by 1912, Stan had a new “sibling” in the person of Ted Leo. The Rum’uns joined the family of another comic, Bob Reed, and became “The Eight Comicques [sic],” but a tour of the Netherlands and Belgium did not go well.

Down on his luck and back in England in July 1912, Stan chanced to meet Alf Reeves, manager of Karno’s American touring company. Reeves offered Stan his old job back—which included another tour of the States, beginning on October 2, 1912. Stan would not return to England until taking a brief holiday in 1927.

The Karno troupe, with Chaplin again starring, was a sensation throughout the States. Film producer Mack Sennett was told about this wonderful new comedian and in May 1913 sent a telegram to the Karno company in Philadelphia: “IS THERE A MAN CALLED CHAFFIN IN YOUR COMPANY OR SOMETHING LIKE THAT…” Chaplin held out for $150 a week, agreed in August to sign with Sennett as soon as he could, and left the Karno troupe in November. On December 29, 1913, he signed the contract to become a player in Keystone Films. By November 1914, he had become a worldwide sensation. Stan, on the other hand, was having a reversal of fortune.

The Karno troupe broke up in the spring of 1914. Stan joined with two other former Karno performers, Edgar Hurley and his wife Ethel (known as “Wren”), in an act called The Nutty Burglars. They played the lowest rungs of vaudeville until Stan met up with two agents, Claude and Gordon Bostock. They knew of Stan’s association with Chaplin and suggested that Stan do an imitation of his now world-famous friend, with Edgar playing Chester Conklin and Wren doing a turn as Mabel Normand. The newly-minted “Keystone Trio” played successfully from February through October 1915, until the Hurleys and Stan parted ways. Stan then joined another married couple, Alice and Baldwin “Baldy” Cooke, in an act called The Crazy Cracksman, which again played small-time vaudeville through 1917. Stan remained friendly with the Cookes for years thereafter—Baldy appears in several L&H comedies—even though the act broke up. That spring, Stan met Charlotte Mae Dahlberg Cuthbert, a singer and comedienne, and they became partners professionally and personally. For the next few years they worked their way up the ranks of vaudeville, often in an act called No Mother to Guide Them, which featured Stan in drag as an old biddy. Another sketch was Raffles, the Dentist.

Laurels Aplenty and Film Debut

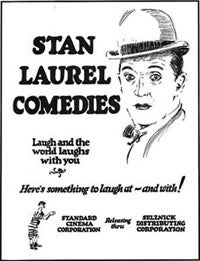

Mae had left behind a husband in her native Australia, and Mr. Cuthbert refused to give her a divorce. “Stan and Mae Jefferson” was too lengthy to fit on theater marquees or programs with a decent type size—and technically, Mae was not Mrs. Jefferson—so a new billing was needed. In their dressing room one night, Mae found an old history book left behind, and opened it. It fell open to an etching of a Roman general, Scipio Africanus Major, who wore a wreath of laurel around his head. Voila—Stan and Mae Laurel. Mr. Laurel would legally change his name in August 1931.

Up to this point, Stan’s entire career existed only in a few photographs, newspaper reviews, and the memories of audiences who had seen him. Fortunately, his talent was about to be preserved on film.

In the summer of 1917, a former producer at Universal named Isidore Bernstein decided to produce a series of short comedies, one unit to star Stan Jefferson (evidently he hadn’t firmly decided on the name change just yet). Only one film, Nuts in May, was produced before Bernstein withdrew from the project, but the film was shown at the Hippodrome in Los Angeles in August or September 1917. In the audience was Carl Laemmle, who offered Stan a contract with Universal Pictures.

The 82 solo films he made through May 1927 provide a fascinating look at his talent outside of the realm of Laurel and Hardy.

Stan alternated between vaudeville and picture work until December 1921, at which point he was determined to work in films only. The 82 solo films he made through May 1927 provide a fascinating look at his talent outside of the realm of Laurel and Hardy. Stan freely admitted in later years that he never quite clicked with the public as a solo film comedian, because he couldn’t create a well-defined character. Indeed, in some films (Man About Town), he’s brash, with more than a trace of Chaplin; in others (West of Hot Dog), he’s a timid simpleton, with the Harry Langdon influence showing.

His best films were parodies, where he could spin a funny variation on an established character. Mud and Sand casts him as the famed bullfighter Rhubarb Vaselino. The Soilers was a very funny spoof of the 1923 feature based on Rex Beach’s novel of the Alaskan Gold Rush, with Laurel and James Finlayson putting a unique spin on the famous brawl that Milton Sills and Noah Beery had enacted in the film. Dr. Pyckle and Mr. Pride, maybe his best solo film, is a wonderfully funny Jekyll and Hyde parody (the misdeeds he perpetrates as Mr. Pride include stealing a boy’s ice-cream cone and exploding a paper bag behind an unsuspecting woman).

Hal Roach and "Babe Hardy"

Stan made these films for a variety of studios and producers, including G. M. “Broncho Billy” Anderson, Joe Rock, and Hal Roach, with whom Laurel had three tours of duty. The first came in May, 1918, when Roach director Alf Goulding caught Stan and Mae’s act at the Main Street Theater in Los Angeles. Roach had been making a series with comedian Arnold Novello, known as “Toto,” which Novello’s health problems had terminated with five films to go on the contract. Goulding suggested that Laurel star in the remaining pictures; Roach agreed and sent a telegram to Stan, who was now in Santa Barbara at the Portola Theater. The five one-reelers were shot between June 11 and July 13, 1918; Stan then made three shorts at Vitagraph supporting comedian Larry Semon before the influenza epidemic forced all the studios to close temporarily, and Laurel went back to vaudeville.

A 1921-'22 series for G.M. Anderson resulted in eight films, most notably The Lucky Dog, which featured Stan as the starring comedian and Babe Hardy in support as a hold-up man; their comic rapport is obvious right from the start. After that, Stan went back to Hal Roach, arriving in February 1923 for a series of 24 films, which lasted through January 1924. The next month, Stan embarked on the first of a dozen two-reelers shot on the Universal lot for producer Joe Rock. They were supposed to have been completed at a rate of one per month, but Rock actually was making the pictures much faster and cheaper than he’d let on to his financiers. Rock finished twelve films in seven months, and pocketed the budgets for the final five pictures, which meant that Stan needed a job yet could not appear in front of the cameras as he was still under contract for that to Joe Rock.

During a weekend break from filming, Hardy severely burned his arm while cooking a roast leg of lamb; Roach suggested that Laurel take his place. After he saw the results, Roach suggested that Stan write himself into the next picture.

The result was that on May 5, 1925, Stan arrived at the Hal Roach Studios for a third time, now under contract as a writer and director under the supervision of F. Richard Jones. Stan was immediately put to work directing James Finlayson in his starring series, and he’d soon be directing the Australian comedian Clyde Cook. In June 1926, Babe Hardy was playing the part of “Summers, the butler” in a Roach “All-Stars” comedy starring Harry Myers, Get ‘em Young. Stan was directing. During a weekend break from filming, Hardy severely burned his arm while cooking a roast leg of lamb; Roach suggested that Laurel take his place. After he saw the results, Roach suggested that Stan write himself into the next picture. With Joe Rock sending a letter confirming that he no longer had any claim on Stan’s services, Laurel was now free to again perform in front of the cameras. By August, Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy were starting to appear in Roach’s “All Stars” comedies, and the rest is history.

The Rest is History

Twenty years of performing on stages around the world and making more than 80 films would be a complete career for many artists, but this was merely a prelude for Stan’s truly great work, the films in which he starred (and helped write, direct and edit without receiving credit) with Oliver Hardy. Fourteen of Stan’s solo films are still missing; a much larger percentage of Hardy’s solo work has vanished. One Laurel and Hardy film is missing entirely—Hats Off, a film which got rave reviews and established the team with the public in 1927. Only three fragments of film and the soundtrack (on disc) exist for the two-color Technicolor MGM feature The Rogue Song, in which the team supported Metropolitan Opera star Lawrence Tibbett. A significant portion of The Battle of the Century, which features the epic pie fight that covered much of the Roach studio backlot, is missing as well. Many of the team’s best-loved films are victims of their own popularity, having been printed and re-printed until the source materials have been exhausted.

Stan spent his life giving the world his talent. We’re still delighting in it 121 years after his birth, 46 years after his passing. His film legacy deserves to be properly preserved. In gratitude for all the laughter his artistry has provided, we hope you can make a contribution to the Archive’s Laurel and Hardy fund. Stan gave us the gift of his talent; we should repay him by helping his work live on for future generations.

Randy Skretvedt is the author of Laurel and Hardy: The Magic Behind the Movies, a book which details the production of each of the team's films through interviews with more than sixty of the participants, unfilmed sequences from scripts, and other studio files. First published in 1987, it was revised in 1994 and 1996; a revised and expanded version is in preparation.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation