By Randy Skretvedt

January 2012 brings the 120th “natal anniversaries” of two of the three most important players in the Laurel & Hardy saga—Hal Roach and Oliver Hardy. (We’ll be marking the 122nd anniversary of Stan Laurel’s birth on June 16.)

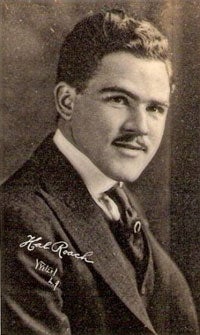

These two Capricorns were very determined young men. Harry Eugene Roach was born in Elmira, New York on January 14, 1892. His mother, Mabel, was hoping that her child would be a girl and wanted to name her Harriet; after her son was born, Mrs. Roach still wanted to name the child Harriet, but wiser heads (including that of father Charles) prevailed. Harry had his name legally changed to “Hal” as a young adult. As children, Hal and his elder brother Jack would be spellbound by the stories that their mother’s father would spin, and later Hal would attribute 90 percent of his success in building film stories to an ability inherited from his grandfather. Young Hal met and shook hands with another master storyteller who lived in Elmira: Mark Twain.

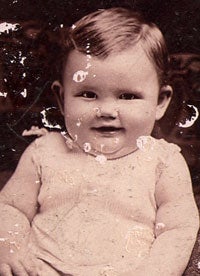

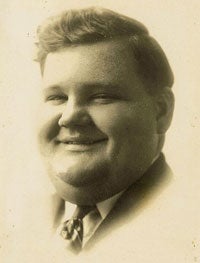

Norvell Hardy was born to former Confederate soldier, local politician and hotelier Oliver Hardy and his wife, Emily Norvell Tante Hardy, in Harlem, Georgia on January 18, 1892. He is said to have weighed 14 pounds at birth; his weight would be a source of acute embarrassment for most of his life, but ultimately it would also become a source of gainful employment. Norvell’s father died before the child was one year old, and later, Norvell adopted “Oliver” as his first name in honor of the father he never knew. While he was often teased about his weight, young Norvell was popular as an umpire at local baseball games, and early on possessed a lovely singing voice. His mother had four children from a previous marriage (Sam, Elizabeth, Emily and Henry), and to support Norvell and his four half-siblings she managed a hotel in Milledgeville, Georgia. Here young Hardy became fascinated by the varied characters who would stay at the hotel, and he would put to good use in his acting the traits of people he’d observed while “lobby watching.”

Careers Begin

When he was 17, Hal Roach’s father told him to go and see the world, and young Hal went off to Alaska, where he worked with teams of pack horses. He drove a truck for a year after that (and was fired for driving it “too fast and hard”), then got a job in construction. This brought him to Los Angeles, where one day in 1911 he chanced upon a newspaper ad offering a dollar a day plus lunch and carfare to anyone who owned Western clothes and wanted to work as an extra in movies. Roach put on his Stetson and boots and took a bus to the 101-Bison studios. On his first day, Roach proved his worth when the director of a scene in a gambling hall didn’t know which way the ball was supposed to spin in a roulette wheel. Roach had seen his share of real gambling halls and knew that the ball was spun in the opposite direction of the wheel—and his salary was immediately increased to five dollars a day.

By 1913, Roach was making $30 a week as an extra at Universal, and rooming with George Marshall (whom he would later employ as a director) and Frank Borzage. Another friend was a young actor from Nebraska by way of San Diego named Harold Lloyd. In 1914, Roach began producing one-reel comedies starring Lloyd; a business partner named Sawyer promised to sell them to the big exchanges in New York. He did so, but didn’t cut Roach and Lloyd in on the profits. Roach chanced to see at a theater one of his films, which been released by Pathé; he got in touch with the company, who wanted more of Roach’s efforts. With partner Dan Linthicum, Roach started making “Phunphilms” for the new Rolin Film Company. The star was Lloyd, first as “Willie Work,” and then as “Lonesome Luke.” The latter character wore the reverse of Chaplin’s outfit (tight trousers, small shoes, baggy coat), and Lloyd disliked it intensely, but audiences loved the films.

Meanwhile, Oliver Norvell Hardy at 18 was managing a movie theater in Milledgeville, and increasingly began to feel that he had at least as much innate acting talent as the comedians whose strenuous efforts he was projecting. “I saw some of the comedies that were being made and I thought to myself that I could be as good—or maybe as bad—as some of those boys,” was the way he put it to biographer John McCabe in 1954. In 1913, Hardy married Madelyn Saloshin (their union would last until 1921), and they headed for the burgeoning movie capital of Jacksonville, Florida, whose studios—in those days of shooting in available sunlight—were almost turning out as much film as their counterparts in Southern California.

Hardy soon found work at the Lubin Studios (he earned five dollars a day, with three days’ work per week guaranteed); his first film, Outwitting Dad, was released April 21,1914. He was billed in this as “O. N. Hardy,” but by the next film, Casey’s Birthday, he had acquired his lasting nickname and the name by which he would be credited in films for the next twelve years—“Babe.” It came from a Jacksonville barber of Italian extraction, who would give Hardy a shave each morning and then rub talcum powder into his chubby cheeks, saying, “Nice-a babeee, nice-a babeee.” His Lubin co-workers teased Hardy about it and called him “Baby” at first, then Babe—and the name stuck.

Babe Hardy and Hal Roach joined forces in May, 1925, their first collaboration being an entry in Roach’s “Spat Family” series called Wild Papa. In that same month, Stan Laurel—having worked for Roach in 1918 and again in 1923-'24—came back for a third tour of duty as a writer and director; he would co-direct Hardy in three comedies between May 1925 and January 1926.

Roach by this time had bought out Dan Linthicum and built a beautiful studio on 19 acres of Culver City land, headquartered at 8822 West Washington Boulevard. Roach had become one of the top producers of comedy short subjects—and he had a lot of competition in the ‘20s—with his “Our Gang” comedies and other shorts starring Charley Chase. Harold Lloyd had moved from the “Lonesome Luke” series to the new “glasses character,” and the phenomenal success of the new persona enabled him to start making features. Lloyd parted amicably from Roach in 1923.

Laurel & Hardy

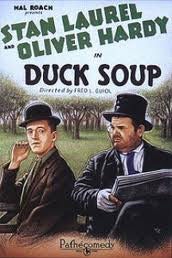

While Roach was still very successful, he was on the lookout for the next big star attraction in comedies; he didn’t know it, but he already had it on the payroll. In February, 1926, Babe Hardy signed a contract as an exclusive performer for the Roach studios; Stan Laurel was still primarily a writer-director, but in late July 1926 he found himself acting again in a Roach comedy, and ironically in a role intended for Babe. Hardy had been cast in Get ‘em Young as a butler, but had burned his right hand and wrist in a weekend cooking mishap. Stan was slated to direct this film, but after Hardy’s injury occurred, supervisor F. Richard Jones asked Stan to play the part himself. Stan was reluctant to do so, but Roach offered a raise and Laurel acquiesced. By September 1926, Laurel and Hardy were tentatively and informally teamed in a short called Duck Soup. A year later, with a film titled The Second Hundred Years, Roach was aggressively promoting his new comedy team of Laurel and Hardy; critics and audiences immediately responded with tremendous approval.

The Roach-Laurel-Hardy collaboration lasted until April 5, 1940 and produced dozens of the funniest and most beloved comedy films ever made. Roach and Hardy were compatible offscreen as well; both were avid sportsmen and loved golf. Roach was also an enthusiastic polo player, hunter and aviator. Roach was instrumental in founding the Santa Anita racetrack—where Hardy wagered (and more often than not lost) many a tidy sum. Each man appreciated the other’s talents. In 1980, Mr. Roach told this author:

“I never saw Hardy at any time try to steal a scene from Laurel; and although Laurel was directing, he never tried to sneak in or steal a scene—if it was Hardy’s scene, Laurel gave it to him. The gestures that Hardy did were his. The tie, his looking into the camera, and the way he did things individually, nobody told him. I never heard anybody, including Laurel, direct him in anything. You didn’t have to tell Hardy what to do; he was a hell of a good actor.”

Hardy had a command of the camera, and a subtlety and natural quality in his acting, that was astonishing for its time and is still impressive today. Sure, Spencer Tracy is great in Adam’s Rib (1949), but watch Oliver Hardy in Block-Heads (1938). Or in Helpmates (1932), or Below Zero (1930), or in anything else. His ability to communicate a whole range of emotions with just a glance is remarkable—and somehow his looking directly at us, breaking that sacrosanct “fourth wall,” never seems gimmicky or forced; it’s a perfectly natural way of communicating his innermost thoughts to us powerfully and succinctly.

Hal Roach and Babe Hardy—two giants of film comedy, combining talents behind and before the cameras to create movies which have delighted audiences for more than eighty years. With your donation to UCLA's Laurel and Hardy Film Preservation Fund, you can help these films survive to entertain many more generations in the future.

Randy Skretvedt is the author of Laurel and Hardy: The Magic Behind the Movies, a book which details the production of each of the team's films through interviews with more than 60 of the participants, unfilmed sequences from scripts, and other studio files. First published in 1987, it was revised in 1994 and 1996; a revised and expanded version is in preparation.

Oliver Hardy (ca. 1892) courtesy of Randy Skretvedt; Hal Roach and Oliver Hardy (both ca. 1914) courtesy of Laurel & Hardy Archive on Facebook.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation