By Richard W. Bann

In 1914 Hal Roach began his career as an independent producer, specializing in comedy. Memorable series were built around star names Harold Lloyd, Our Gang, Charley Chase, Will Rogers, Thelma Todd, Harry Langdon, and Laurel & Hardy. Anyone who has seen their work is likely to agree on the importance of preserving these films for future generations to discover, study and enjoy. Frustrated fans who know and care about saving and sharing the films have long asked how they can aid in this effort. Now there is a way everyone can get involved.

UCLA—as the story below will make clear—now has the best surviving nitrate on many Laurel & Hardy titles and is beginning a multi-year project to restore these films to their original glory. They are soliciting donations large and small from anyone and everyone all over the world who wants give something back and feel as though they have made a contribution to propagating the spirit and genius of Laurel & Hardy, so that the films will survive and continue to entertain as many future generations as possible. That this work is necessary is due to decades of benign neglect, when the only thing that mattered was to exploit the library, and preservation efforts have been sporadic or inaccessible.

Hal Roach Studios

Until his son bankrupted the organization in 1960, Hal Roach Studios had more by accident than by design saved certain original 35mm camera negatives, dupe negatives, fine grain master positives, as well as other prints, even while licensing footage to sub-distributors.

For example, in 1943, producer George Hirliman’s Film Classics contracted with Roach to re-release much of the studio’s post-1928 product. Obliged by contract to remove the MGM trademarks, the imaginative, original-design presentation titles sequences were thoughtlessly tossed.

Film Classics was also guilty of re-editing the pictures, a notable example being Pack Up Your Troubles (1932). Sometimes they added music where it did not belong, such as taking the titles music track from Busy Bodies (1933) and marrying it with the titles action sequence from Men o' War (1929). This muddy-looking version, like so many others which Film Classics tampered with, have remained in circulation for more than half-a-century because subsequent licensees inherited the material.

We know, generally, that even though they were important corporate assets, film materials at studios have seldom been the beneficiary of careful maintenance. Movies were regarded as disposable, perishable entertainment. The really tortured existence of the Laurel & Hardy library began as bankruptcy approached and the already greatly diminished pre-print material began to wear out from over-use and deterioration.

What has happened to all these thousands of film elements over the years? What have the results been, particularly with respect to Laurel & Hardy? And what can the rest of us do—if anything, at this late date—to help save what is left?

The Prints

Many successive licensees and sub-licensees in television were given lab access to reprint the Film Classics negatives, which in some cases were actually altered camera negatives! There was never any stipulation as to licensees being required to manufacture their own new printing materials to fulfill 16mm TV syndication sales around the country. With a tangled array of domestic licenses granted to Governor TV Attractions, Regal Television, Inter-State Television, Prime TV, National Telepix, Walter Reade-Sterling, and many others, the film library was kicked around through many more unsure hands. For foreign distribution, the original negatives had also been widely re-packaged, reissued, re-printed and over-printed.

In 1968 as the company reorganized, Hal Roach went to Wall Street in search of production funding. Buried in the prospectus was a declaration that $50,000 of the proceeds would be dedicated to transferring certain negatives from nitrate to safety stock. Instead, to save money, all the nitrate was deposited at the Library of Congress.

When the collection was in Library of Congress' custody, some of the negatives were printed onto 35mm safety stock as one-light or only partially-timed masters, but not on polyester-based safety stock. During the 1980s, Jim Harwood cared for this material, and remembers:

“I had to junk one of the reels of the original negative of Laurel & Hardy’s From Soup to Nuts (1928) due to heavy deterioration. It was a very painful thing to do, but the film was crumbling to powder.”

When I visited the Library of Congress in 1983, the indispensable David Parker of the curatorial staff explained:

“The Roach collection, although highly valued by me, personally, is the most intractable library and the worst mess we have, a real Chinese puzzle. Someone actually registered a complaint with the union over being assigned to work on the Roach collection.”

One TV licensee did invest in preparing new printing negatives. Saul Turell’s Janus Films made a conscientious attempt to reconstitute faithful, new 16mm Laurel & Hardy negatives for their own use. Their effort took two years. The results were mixed. In Way Out West (1937), e.g., sound levels varied, there were jump cuts, the stream-crossing finale was incomplete, and the original end title was replaced.

Popular Resurgence

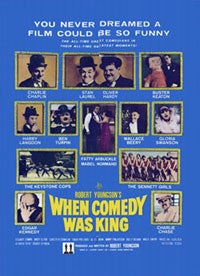

From 1957 through 1970 filmmaker Robert Youngson mined the Roach library of silent comedies to produce a succession of compilation films, including The Golden Age of Comedy (1957) and When Comedy Was King (1960). Youngson’s success heralded a renaissance of interest in silent comedies, and Roach licensed many 8mm and 16mm non-theatrical distributors to serve the domestic market for college film societies, churches, libraries, civic groups, and home entertainment. Such small business operations included Official Films, Erko of Hollywood, Library Films, Film Classic Exchange, Entertainment Films, Select Film Library, Exclusive Movie Studios, many others. During the 1970s when I worked for Roach's principal non-theatrical licensee, Blackhawk Films, I learned that while the company mastered from Roach’s 35mm preprint material, it was only for a single pass to create either a reduction dupe negative or fine grain. Also, founder Kent D. Eastin was steadfast on the point of replacing all the artistic original title card designs, and replacing them with drab standardized Blackhawk Films titles.

After Hal Roach Studios emerged from bankruptcy, in 1971 the equity was split between Eastern and Western Hemispheres. In the latter, rights passed from Hal E. Roach, Sr., successively, to Earl Glick’s Portcomm Communications, Robert Halmi’s RHI, Hallmark Entertainment, then back to RHI. Overseas, the copyright proprietor has for the past forty years been CCA, a company originally controlled by the founders of what became the German KirchMedia GmbH & Co.

Restoration Begins

Working for CCA during the 1980s through 2002, I was able to supervise the rescue and preservation of the nitrate film elements in the Hal Roach library. We are the only company or institution or archive anywhere in the world which has ever undertaken to restore and preserve and distribute the surviving film materials that constitute the entire post-bankruptcy library of Hal Roach Studios.

"The preservation materials, as good as they are, are in Munich and inaccessible to American audiences..."

The work was performed in Los Angeles at Film Technology Company, by a knowledgeable and dedicated colleague from our days together at Blackhawk Films, Bill Lindholm. We decided against wet-gate printing, which hides more visible scratches and wear than does diffusion filter printing, but the image would not have been as steady or as sharp. Nor was any kind of digital cleanup performed, which is an option (albeit an expensive one) under consideration by UCLA Film & Television Archive. In any case, the preservation materials, as good as they are, are in Munich and inaccessible to American audiences (although our work has been used by domestic licensees Cabin Fever, Vivendi, and TCM—but, significantly, not for the less than stellar-looking Laurel & Hardy films on the recent TV festival). UCLA now houses the surviving nitrate materials from RHI in its state of the art vaults.

Laurel & Hardy are the greatest comedy team, who made the greatest comedies of all time, and we owe them and their legacy no less than the best effort we can make to preserve their work as best as is humanly possible—even if the memorable ending of Hog Wild (1930) was shot on campus at USC, and not at its cross-town rival, UCLA.

If 35mm exhibition prints from UCLA preservation efforts are made available for audiences throughout America, the Laurel & Hardy films will at last be shown again the way they were intended to be seen by their creators—restored, uncut, uninterrupted, on a theatre screen, in the dark, in front of a live audience. Where they come to life, where the love shows, where the magic happens, and where future generations yet unborn will be grateful beyond words, that we, all together, did this work, and just in time. Now is the time.

A more detailed history of the physical inventory created by Hal Roach Studios, and its disposition up to the present, will be available soon at the Official Laurel & Hardy Website, www.laurel-and-hardy.com.

Richard W. Bann is the co-author with John McCabe and Al Kilgore of Laurel & Hardy, and with Leonard Maltin of Our Gang. He is consultant to the copyright proprietor of the Hal Roach library in the Eastern Hemisphere, and arranged to have the nitrate collection deposited at the UCLA Film & Television Archive.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation