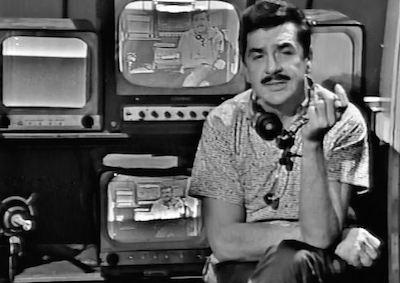

The New York Times wrote in its 1962 obituary for Ernie Kovacs (1919-1962) that he “had the sort of talent for which television was invented.” And where television didn’t suit Kovacs’ anarchic personality, he simply reinvented it. The writer-director-comedian started out in 1941 on radio at a station in Trenton, New Jersey where he became a local legend for his remote reports which required lugging cumbersome recording equipment around town, a technical burden that Kovacs readily bore to give rein to his restless creative energy. In 1950, he leapt to television where he defied and redefined the new medium’s conventions just as they started to form. On Philadelphia's WPTZ, he launched 3 To Get Ready, the first-ever morning wake up show, which led to NBC’s It’s Time for Ernie, a 15-minute wildly improvisational, comic assault on the boundaries of television itself. He broke the fourth wall, sure, but once through, he led his audience back into a wider, electronic world of imaginative possibility where anything could happen—especially if it got a laugh. A consummate technician and prolific workaholic, Kovacs and his loyal crew and players—including performer and partner Edie Adams—executed his often technically challenging sketches with spontaneity and joy, creating some of television’s most uproarious characters and screen-bending surrealist images. From his local beginnings to nationally broadcast prime-time specials—and later film roles—Kovacs inspired his contemporaries, including Jack Lemmon, Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks, and his undeniable influence can be felt in generations of television comedy to come from Monty Python to Saturday Night Live to Pee-Wee’s Playhouse and Mystery Science Theater 3000, not to mention the late night pantheon of Johnny Carson, David Letterman, Conan O’Brien and Jimmy Kimmel. For all this, Kovacs’ work and legacy might have disappeared if not for the efforts of Edie Adams who, in the decades after her husband’s death in a car accident, worked to buy back the original recordings of his shows from the networks, some of which had begun re-recording over them to save money on video tape. The Archive is pleased to celebrate the centennial year of this too often unheralded pioneering postmodernist.

Special thanks to Josh Mills; Mark Quigley, UCLA Film & Television Archive; Rob Stone, Library of Congress.

You are here

Kovacsland Forever: Ernie Kovacs Centennial

January 18, 2019 -

January 19, 2019

January 19, 2019

Past Programs & Events

| Title | Date and Time | Location | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Ernie Kovacs: Tele-visionary at 100 |

Friday, October 4, 2019 - 7:30 pm | Billy Wilder Theater |

|

Our Man in Havana |

Saturday, January 19, 2019 - 7:30 pm | Billy Wilder Theater |

|

Kovacs in Television Land |

Friday, January 18, 2019 - 7:30 pm | Billy Wilder Theater |

To report problems, broken links, or comment on the website, please contact support

Copyright © 2025 UCLA Film & Television Archive. All Rights Reserved

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation