“We were scarred in so many ways.” —Julie Dash, The Diary of an African Nun Q&A (11/19/2011)

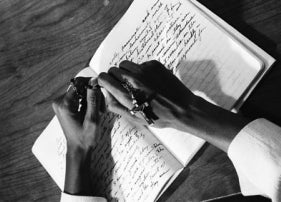

During the Q&A following the screening of Julie Dash’s The Diary of an African Nun (1977), an audience member commented that the film’s music created a sense of a space and cultural location. For a film shot entirely in Los Angeles, Dash’s use of music to create this space points to the filmmaker’s ingenuity in mobilizing limited resources to create an environment on screen that reads as Uganda, the film’s setting. The exteriors for the film, Dash said, were shot in an area in Culver City that is now the site of Fox Hills Mall, while the nun’s cell was Dash’s own apartment in Marina Del Rey that she stripped-down to shoot the interiors. It is remarkable that these beautifully lit and composed shots were achieved with a two-person team: Dash and Barbara O., the actress playing the nun. As Dash adjusted the lighting, Barbara O. would take the light meter reading from her position, hide the meter, and they would shoot the next shot. For film school students, this kind of shooting scenario probably rings very true, but many people are not aware of the true scale of filming situations for student projects.

The results here are tightly lit and framed shots whose economy conveys the interiority of the nun’s conflict. Her ascetic environment contrasts with the sounds and lights of life and community taking place outside of her cell, which she longs for even as the demands of her vocation require that she remove herself from that sphere. When she imagines what is happening outside, she draws from her childhood memories and experiences of her family and community, indirectly reflecting on the fact that becoming a nun requires that she deny her own family, culture, and history. Taking the habit, then, speaks to religion as an armature of colonization where it seeks to displace indigenous cultural practices and social organization in order to implant its own narrow and limiting ideologies, as confining and stifling as the room in which the nun’s conflicting thoughts and desires play out.

Dash’s Project One film indicates many of the themes that would be present throughout her prolific career. Although Dash confessed during the Q&A the many “student film” mistakes that she saw in the film, such as it being “very talky,” it nonetheless remains a very personal early effort. Diary of an African Nun is, in Dash’s words, a condensed version of the short story by Alice Walker that is featured in the collection In Love & Trouble: Stories of Black Women. Dash chose to adapt this work for several reasons. First of all, she had read a great deal of Walker’s work as an undergrad, and she quickly became Dash’s favorite author. Dash was inspired by the images of Black women that Walker offered up, which she had never seen before, as well as the story’s aforementioned critique of the colonialism of religion. Seeing herself as unable to write like Alice Walker, Dash chose to film it instead.

In addition, Dash spoke during the Q&A of wanting to “start [as a filmmaker] in West Africa.” After a childhood of not seeing Black people on television, she offered the epigraph to this post: “We were scarred in so many ways.” For Dash, it seems that The Diary of an African Nun is something of a restorative project. First of all, it provided a complex, multifaceted image of a Black woman in a medium devoid of such iconography. In addition, the film acknowledged that there was a Black history that started before slavery—that Blackness did not suddenly “just pop up.”

—Karrmen Crey and Jenni Fong

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation