KTLA News: “Undersheriff Sherman Block denies pattern of brutal activity by deputies” (1979)

Guest writer Trudy Goodwin has served as a Los Angeles organizer, legal observer, cultural arts director, journalist and radio producer. She served as the community consultant for Archiving the Age of Mass Incarceration, a collaboration between Million Dollar Hoods and the UCLA Institute of American Cultures. Today, she works with healers, artists, visionaries and change-makers to co-create a movement in support of families impacted by violence. This blog was made possible by a grant from the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation.

The purpose of this blog is to explore the UCLA Film & Television Archive’s KTLA News Project: “Incarceration, Policing and Crime (1970–1980),” focusing on newly digitized and accessible news stories primarily addressing in-custody deaths and police brutality. By comparing these historical reports and noting how they relate to personal experiences, I aim to reveal the long history that continues of this troubling phenomenon. I will share my own experiences with police brutality and the deaths of Black individuals in custody, particularly in Southern California.

The historical KTLA collection documents wrongful deaths of incarcerated people and police violence against Black and Brown communities, particularly since the mid-1970s. These records show both the community’s outrage, families’ pursuit of justice and law enforcement’s reluctance to address the ongoing dilemma.

A Historical Context of Struggle

For much of my life, I have been aware of the fight against police brutality in Los Angeles. My mother, Idalah Grace Perkins (pictured, right), a civil rights activist who, starting in the early 1960s, played a crucial role in establishing the local United Civil Rights Committee. This committee not only fought against racial segregation and discrimination but also proactively addressed police brutality through a dedicated subcommittee, “Stop Police Brutality.” My childhood was steeped in activism, as I participated in protests aimed at obtaining civil rights for all.

LAPD Chief Daryl Gates and LA Sheriff Sherman Block, featured in the news footage, stand as symbols of the opposition my mother and her colleagues faced while calling for the end to police brutality. On November 6, 1979, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors held a hearing at which community members shared concerns about excessive force. Many urged the creation of an independent review board for these issues. In response, Sheriff Peter Pitchess provided a report, and Undersheriff Sherman Block shared statistics. Block highlighted the rise in violent crime and explained that with this increase, it’s tough to expect fewer confrontations. Block noted that complaints compared to arrests were minimal, suggesting that misconduct among deputies was not widespread. The comments by Undersheriff Block resonate with the challenges my family encountered while combating police brutality.

Highlighting Specific Cases

The Archive’s KTLA News holdings include disturbing accounts of police killings, particularly of young Black individuals. One notable case is that of Ferdinand Bell, who died in the custody of the LA County Sheriff's Department under suspicious circumstances. An autopsy conducted by a private pathologist revealed signs consistent with manual strangulation, conflicting with the Sheriff's account that suggested Bell had acted violently while being booked.

When Bell was booked on suspicion of reckless driving, he was later taken from jail to USC Medical Center after exhibiting irregular breathing. Tragically, he died there. The official investigation into his death was hampered by a lack of transparency from the coroner’s office and the Sheriff's department, raising serious questions about the circumstances surrounding his death.

KTLA News: “Excessive force by LA County Sheriffs suspected in death of Ferdinand Bell while in custody” (1978)

Terence Keel, Ph.D., UCLA professor of Human Biology & Society and African American Studies, and founding director of the UCLA Lab for BioCritical Studies, an expert on police violence, explains on UCLA Radio how historical and political contexts shape narratives surrounding custodial deaths.

This violence is often minimized or rationalized in official records, as medical examiners rely heavily on initial police reports that may downplay police involvement in these tragic deaths.

The Systemic Nature of Violence

My family’s experience with police-related deaths also resonates here. In the 1990s, my nephew Mark Ingram (pictured, right) died under suspicious circumstances while incarcerated at California State Prison, Corcoran. Initially reported as a heart attack, it was later revealed through a private autopsy and inmate testimonies that Mark suffered from hypothermia after being locked inside a prison freezer. My family successfully sued the state of California for the wrongful death of my nephew and the attempted coverup by the state’s coroner’s office.

Historical examples abound, such as the killing of David Aguayo, a 16-year-old Mexican American boy, shot by deputies under dubious circumstances. The narrative surrounding Aguayo’s death was framed to justify police actions, a common theme echoed in community responses and protests against police violence throughout the years.

Personal Reflections and Community Experiences

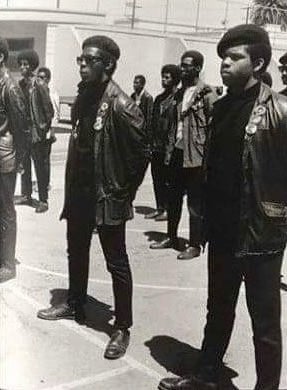

My personal encounter with police violence began in 1968 when a family friend and member of the Black Panther Party, Steve Bartholomew (pictured, right side of image), was killed in what was characterized as an LAPD ambush. The shock of learning about his murder shattered my trust in law enforcement. This personal trauma informs my understanding of the ongoing threat that police violence poses to Black individuals.

The archived footage and reports from UCLA not only serve as a historical account but also validate the fears that many Black and Brown individuals harbor regarding interactions with law enforcement. The testimonies of community members reflect a persistent call for accountability and justice that has echoed through the decades. One such interview with Commissioner Stephen Reinhardt exemplified the City’s response to residents’ calls for police oversight. At Los Angeles City Hall, Police Commissioner Reinhardt announces an expanded role for the Commission in investigating officer-involved shootings. He emphasizes its non-political nature and authority to implement policy changes. Police Chief Daryl Gates speaks about the department’s record in investigating cases brought against officers, and expresses his personal reservations about the new system and the protection of police rights.

The archived footage and reports from UCLA not only serve as a historical account but also validate the fears that many Black and Brown individuals harbor regarding interactions with law enforcement. The testimonies of community members reflect a persistent call for accountability and justice that has echoed through the decades. One such interview with Commissioner Stephen Reinhardt exemplified the City’s response to residents’ calls for police oversight. At Los Angeles City Hall, Police Commissioner Reinhardt announces an expanded role for the Commission in investigating officer-involved shootings. He emphasizes its non-political nature and authority to implement policy changes. Police Chief Daryl Gates speaks about the department’s record in investigating cases brought against officers, and expresses his personal reservations about the new system and the protection of police rights.

The Role of Activism and Policy Recommendations

Throughout the 1970s and ’80s, community leaders rallied against police brutality, demanding an independent civilian review board to address complaints. Assemblywoman Maxine Waters, a prominent voice during that era, called for federal investigations into police killings, emphasizing the need for comprehensive reform.

Despite some progress, the struggle for justice continues today. The statistics remain alarming, with Black men still dying in custody at disproportionately higher rates compared to other ethnic groups. The prison abolition movement advocates for redirecting resources away from punitive systems and towards community support, mental health services and crime prevention initiatives.

KTLA News: “Assemblywoman Maxine Waters speaks out against police violence on first anniversary of Eula Love shooting” (1980)

Current Landscape and Future Directions

Reform efforts are ongoing, but unevenly executed. Many community members advocate for police accountability, greater transparency into incidents of use of force, and policies that promote community well-being over punitive measures.

To truly honor the memories of those lost to police brutality and in-custody deaths, we must persist in our advocacy for systemic change. The work is far from over, but through awareness and collective action, we can strive to create a more just society, accountable to all its members, particularly those most vulnerable.

In conclusion, by examining UCLA’s archive of KTLA News footage, we not only highlight the long-standing issues of police brutality and in-custody deaths but also inspire continued action against these injustices. Our fight is not just for remembrance but for systemic change that prioritizes human dignity and community safety above all. Can police abolition be the answer? On The Daily Show, an interview with Derecka Purnell, lawyer, writer and organizer, examines the possibility of a nation without police.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation