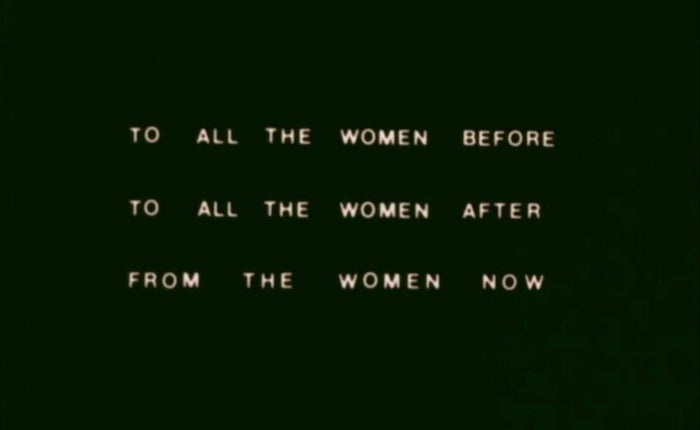

We're Alive (1974)

Our guest writer is Rox Samer, a feminist, queer, and trans media and cultural studies scholar; remix artist; and documentary filmmaker. They currently teach at Clark University as an Assistant Professor of Screen Studies in the Visual and Performing Arts Department. In 2016, they completed a Ph.D. in Critical Studies at the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts and a Graduate Certificate in Gender Studies. In March 2022, Duke University Press published Rox’s monograph, Lesbian Potentiality and Feminist Media in the 1970s.

A new digital restoration of We're Alive (1974) screens at the Billy Wilder Theater at the Hammer Museum on Saturday, January 28, 2023 at 7:30 p.m. with the filmmakers and other guest speakers in person. Free admission. Learn more.

We’re Alive was the culmination of a six-month-long weekly workshop at the California Institute for Women (CIW), 60 miles east of Los Angeles, led by the Women’s Film Workshop of UCLA.1 In making the film, imprisoned women (and quite possibly others imprisoned at this “women’s prison”) gained technical, creative, and organizational skills, learning how to operate cameras, record sound, and structure a documentary. As a voiceover announces at the start of We’re Alive, “This film was made by women inside and women outside working together. Every Sunday for six months we met in a classroom at the prison where we planned the film and photographed it on videotape. Everyone operated the camera, and the songs were written, performed, and recorded by women inside.” This agency of planning and photographing a film was more than a matter of vocational training, of gaining skills they might use upon release. Interviewing and filming one another, it presented a rare opportunity for such prisoners to testify to their experiences of incarceration and the unjust economic and social structures that landed them there. We’re Alive is one of a small handful of feminist prison documentaries of the 1970s, and it shares with Songs, Skits, Poetry, and Prison Life (the women of the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility For Women/Women Make Movies, 1974) and Inside Women Inside (Christine Choy and Cynthia Maurizio/Third World Newsreel, 1978) the thesis that women’s prisons, far from rehabilitating prisoners as they claim to, served to quash Black women’s very hope for freedom. In the face of routine state violence, the activity of making documentaries defied gendered expectations of apolitical resignation.

We’re Alive’s critique of the myth of rehabilitation is articulated most strongly in its section on recidivism. Here, as in most of the film’s interviews, the CIW women appear in handheld medium shots and close-ups cut together with a few tracking shots and pans, which reveal them to be seated in large circle, much like that of a consciousness raising group. Soon after a title card declares, “70 per cent [sic] who leave CIW come back,” a Black woman with sunglasses and expressive hands explains that the work of the prison is quite the opposite of rehabilitation. Rather than helping one grow and gain skills, “The state brings you in here and all of a sudden you’re totally dependent on the state, you know, for everything.” The camera zooms in on her hands, which subtly but firmly punctuate her words with their small gestures. Her right hand, the more emphatic, leaves the frame, and the camera stays on her left, where her thumb and forefinger press circles as she explains that this provision at the hands of the state is a form of conditioning: “And I think that subconsciously they gear your mind towards having it all the time. You don’t have to worry about your meals, because someone over there’s gonna cook. You don’t have worry about clean sheets on your bed, you don’t have to worry about anything. Consequently, it makes you dependent on the state.” As the camera zooms back out and slowly tracks back up her body from her hands to her face, she sets the stakes of such dependency and the recidivism it encourages through the gendered personification of the state, generating laughter in acknowledgement of the truth of her characterization from off-screen: “She’s just a great big-armed mother [laughs with others laughing off-screen]. And there’s really no warmth from her, there’s no sincerity, there’s nothing, you know. And they totally destroy a person.”

In moments like this, Black women theorize the functioning of structural racism by way of the prison industrial complex, whereby they, in the words of Audre Lorde, were never meant to survive.2 And by making this analysis on video with a fellow cast and crew of similarly situated others, imprisoned Black women’s arguments are contextualized as that of a community thinking and working to create change for themselves and others like them. Many of the points made in these documentaries either had been made or would soon be made by the few famous women political prisoners or in the women’s prison newsletters.3 But We’re Alive, Songs, and Inside Women Inside circulated their ideas among a wide women’s movement audience and did so through the uniquely affective qualities of 16mm film and black and white video.

Footnotes

1 Karlene Faith and the Women’s Prison Project Los Angeles, Inside/Outside: An Account of the Women on Wheels 1976 Tour of California and Women’s Struggle to Bring Their Culture to Sisters in Prison (Culver City, CA: Peace, 1976), 15.

2 Audre Lorde, “A Litany for Survival,” in The Black Unicorn: Poems (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.), 31-32.

3 For further analysis and greater contextualization of my analysis here, see my chapter, “Producing Freedom: 1970s Feminist Documentary and Women’s Prison Activism,” in Lesbian Potentiality and Feminist Media in the 1970s (Duke University Press, 2022), 90-137.

Watch the film:

Watch the post-screening conversation:

Additional reading:

Blog: “The Whole System”: “We’re Alive” and Feminist Anti-carceral Struggles

Blog: Interview: “We're Alive” and Experiences of Incarceration at CIW

UCLA Magazine: The Second Life of ‘We’re Alive’

UCLA Newsroom: Injustice remains: 48-year-old women’s prison documentary shows how little has changed

< Back to the Archive Blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation