Savannah (1989)

Our guest writer is Hayley O’Malley, Assistant Professor and Director of Graduate Studies at the University of Iowa Department of Cinematic Arts. Her current book project, titled Dreams of a Black Cinema: African American Writers’ Experiments with Film Since the 1960s, is an archival history that reconstructs the rich but largely forgotten dialogue that took place between African American literature and film from the late 1960s to the early 1990s. Here, O’Malley discusses the creative output of Anita W. Addison, a UCLA alumna who contributed to the groundbreaking L.A. Rebellion Black cinema movement before joining the executive ranks of network television. This blog was made possible by the Myra Reinhard Family Foundation.

“I want to live a great life, and that means I never want to do the same thing twice.”—Anita W. Addison.

Anita W. Addison played an important role in shaping American television in the 1990s. As a producer at CBS and Warner Bros., Addison—who was one of the few Black women executives in network television—produced a multitude of popular shows and directed numerous television episodes and made-for-TV movies.1 Yet although her career mainly revolved around commercial television, the recent recovery and digitization of Addison’s first film, Eva’s Man (1976), which she made as an M.F.A. student at UCLA, firmly locates her creative roots in the avant-garde film culture of the L.A. Rebellion, alongside independent filmmakers such as Julie Dash, Charles Burnett, and Haile Gerima.2 Addison’s participation in such a wide range of different media scenes across the arc of her career highlights the pluralism of Black film and media, and her behind-the-scenes work as a producer reveals the myriad forms of cinematic labor and creativity in Black women’s film history.

Addison’s Eva’s Man is a radical film. It is an adaptation of part of Gayl Jones’ 1976 novel of the same name, in which a Black woman murders and castrates her lover and refuses to tell a white psychologist why.3 Addison’s 13-minute, black-and-white film is as challenging and aesthetically experimental as its source material. Addison combines handheld camerawork, jarring point-of-view shots, and appropriately hazy, sometimes surreal images to create a searing portrait of sexual abuse and traumatic memory. The film does not ask viewers to identify or empathize with Eva (Louise Johnson), but instead visually and sonically recreates the affective intensity of Jones’ prose and the lives it represents.4 Addison’s UCLA classmate Bernard Nicolas recalls how committed Addison was to bringing Jones’ story to the screen: “There was not much Black feminist work being done at our school at the time,” Nicolas told me by email, and “Anita’s film was appropriately shocking.”5 As more Black women began to enroll in UCLA’s film program, such Black feminist filmmaking became more widespread,6 and Addison’s Eva’s Man should be recognized as part of a vanguard of Black feminist films by Julie Dash, Barbara McCullough, Alile Sharon Larkin, Carroll Parrott Blue, Melvonna Ballenger and others that challenged the racial and gender norms of Los Angeles filmmaking, both at UCLA and beyond.

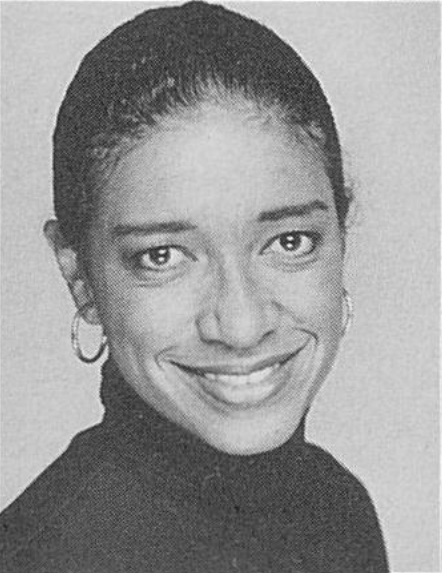

Addison, center, in a 1998 New Yorker profile of female executives in the entertainment industry.

Eva’s Man was also one of the first film adaptations of African American women’s literature made by a Black woman. Previous efforts to bring Black women’s writing to the screen had often been frustrated: Zora Neale Hurston, who was a documentary filmmaker as well as a writer, tried but failed to sell her novels to Hollywood in the 1930s and ’40s, while Lorraine Hansberry wrote the screenplay for A Raisin in the Sun only to see most of its political radicalism removed in a 1961 Hollywood film directed and produced by white men.7 In the 1970s, similarly, Maya Angelou tried repeatedly to adapt and direct a film of her best-selling memoir I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, but without success. In light of that past, Addison’s adaptation of Eva’s Man is an important part of the history of both Black women’s film and Black women’s literature.

Eva's Man could achieve that fusion of Black women’s literary and cinematic aesthetics, I think, in part because Addison made it as a student short film. Addison was not the only Black woman film student at the time who was inspired by Black women’s writing. Melvonna Ballenger, for example, wrote and tried to film a teleplay version of Toni Morrison's 1970 novel The Bluest Eye.8 And Julie Dash has often described how the literature of Morrison, Toni Cade Bambara, and Alice Walker “nurtured and nourished her” as a college student and motivated her to become a filmmaker so that she could bring those kinds of stories about Black women to the screen.9 Indeed, in 1977, perhaps inspired by Addison’s Eva’s Man, Dash adapted Alice Walker’s short story “The Diary of an African Nun” as her second film at UCLA. Dash wrote to Walker for permission to shoot the film, but when Walker did not respond, Dash forged ahead anyway, because she was so committed to seeing the story’s protagonist “come to life.”10 It is unclear whether Addison communicated with Gayl Jones while making Eva’s Man, but either way, her student production—arguably more even than subsequent big-budget film adaptations of novels by Hurston, Walker, and Morrison—showcases the aesthetic and political potential of creative networks between Black women writers and filmmakers.

Addison passed away in 2004, and even with the recovery of Eva’s Man, details about her UCLA days remain thin. In 1977, the Daily Bruin reported that Addison co-produced an episode of Bruin Focus for a television production course.11 And in 1980, she worked with Ivy Sharpe, Geoffrey Gilmore, and Billy Woodberry on lighting for Bernard Nicolas’ short film When Gidget Meets Hondo, which reimagines the LAPD’s 1979 murder of Eula Love, a Black woman, as the shooting of a white woman in order to ask, in Allyson Nadia Field’s words, “whether such police brutality would be tolerated if the victim were a middle-class white woman.”12 Nicolas, in fact, was the only filmmaker who shared specific anecdotes about Addison in the extensive oral histories of the L.A. Rebellion conducted by Field, Jacqueline Najuma Stewart, and Jan-Christopher Horak. In his interview, Nicolas described a film project in which Addison and “her best buddy,” likely Sharpe, wanted to create the impression of people being on a cloud.13 So they stretched a nylon tarp over a sound stage pit at UCLA, the actors climbed on top, and they lit it from below. In the middle of the scene, however, the nylon burst into flames. Nicolas flipped the circuit breaker, they put out the fire, and no one was hurt. “But that’s how it was,” Nicolas recalled, “It was an adventure!”14

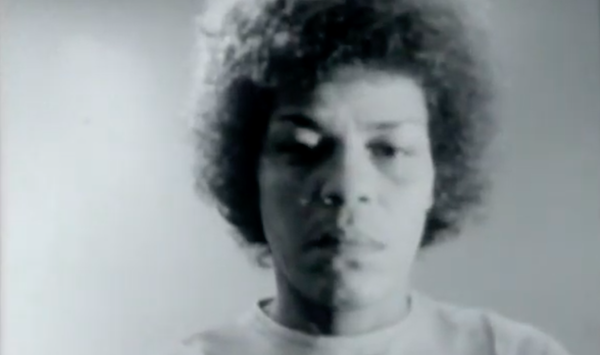

Penny Johnson in Savannah (1989)

In the mid-1980s, Addison embarked on a different adventure: She traded student filmmaking for a research job at Paramount Television, and by the end of the decade, she was the head of dramatic development at Lorimar Television, an affiliate of Warner Bros. “I want to live a great life,” she later told the Los Angeles Times, “and that means I never want to do the same thing twice.”15 She was not, however, ready to stop directing, and in 1989, she finished her second film, Savannah.16 The film operates in the mode of speculative fiction to dramatize the story of Whitney (Penny Johnson), a Black woman with a split personality whose presentation as a hyper-competent career woman depends on her rejection of traditional African beliefs and spirituality. Both Paramount and Lorimar receive production credits in the film, and although Addison may have begun making it while she was at UCLA, the production values are noticeably higher than most student films. And yet, Addison also leaned on her UCLA network to make the film: Her classmate Alfreda Masters served as assistant director, before Ivy Sharpe took over,17 while various members of Masters’ family, including her young daughter, appeared in or helped to crew the film. Indeed, Masters has one of the few existing copies of Savannah, because she asked Addison to bring it with her to a Thanksgiving celebration “to show the family since most of them were in it.”18

Subsequently, in the 1990s, Addison focused exclusively on television, as the smaller screen seemed to offer more—though still not nearly enough—opportunities for Black women filmmakers.19 In a 1999 series of Los Angeles Times articles about race and representation in television in 1999, Greg Braxton, a Black journalist, repeatedly quoted Addison on the state of things. “The good news,” she said, “is that there is absolutely more of an opportunity for diversity, all the way from BET [Black Entertainment Television] to the WB and UPN. There is more of a recognition of the value of the African American experience.”20 Addison’s own resume, however, includes many shows that were seemingly much more interested in white America, from Sisters and EZ Streets,21 both of which Addison produced, to ER and Knots Landing, for which she directed select episodes.22 She may well have pursued such projects to demonstrate her range, but within the world of 1990s network television, working on white-oriented, or “mainstream,” shows may simply have been unavoidable. It was a world that Addison was actively trying to change: In a 1997 article, Emmy celebrated her behind-the-scenes work to increase opportunities for women and people of color and quoted her as saying, “I have given blind script commitments to writers who I know wouldn’t have gotten a chance if someone of color wasn’t in this office. But conversely, I won’t help someone just because they’re African-American. They have to be good.”23

Oprah Winfrey and Maya Angelou in There Are No Children Here (1993). Credit: ABC.

Addison also directed two made-for-television movies in the 1990s, There Are No Children Here (1993) and Deep in My Heart (1999). Both are social realist melodramas deeply engaged with race. No Children, which was adapted from Alex Kotlowitz’s best-selling book, tells the story of a Black family in inner-city Chicago and was one of the first completed projects by Harpo Studios, Oprah Winfrey’s production company. Winfrey herself starred in the film, with Maya Angelou taking a supporting role as her mother—several years before Angelou finally directed her own first feature film, Down in the Delta (1998).24 Addison’s Deep in My Heart tackles even more controversial subject matter, with Anne Bancroft earning an Emmy Award for portraying a white woman who is raped by a Black man and then gives up her baby for adoption. Much of the movie follows that child, now an adult, searching for her birth mother. Though they are stylistically far apart, Eva’s Man and Deep in My Heart, the two bookends of Addison’s career, demonstrate her overarching desire “to understand human frailty and appreciate it.”25

For all Addison’s success in commercial television, it is hard not to speculate about what her career could have been if the film and TV industry provided more opportunities for Black women filmmakers like her. In the 1970s, Addison gravitated toward Gayl Jones, whose novels Toni Morrison had edited and championed,26 and in the 1990s, Addison collaborated with Oprah Winfrey at precisely the same time that Winfrey was searching for someone to direct a film adaptation of Morrison’s novel Beloved (1987). It is unclear whether Winfrey ever considered Addison, but what if she had? And what if Addison had made a Beloved film in the vein of her earlier, experimental adaptation of Eva’s Man? That would be a movie to see.

—Hayley O'Malley

Special thanks to David Byrd and Alfreda Masters.

Watch Eva's Man (1976) on YouTube (note: the video is age-restricted, sign in required)

Watch Savannah (1989):

Footnotes:

1 Mary Rourke, “Anita Addison, 51; Pioneering TV Network Producer, Director,” Los Angeles Times, January 30, 2004.

2 Carter Mathes, a professor at Rutgers University, reached out to Addison’s partner David Byrd and as a result of their conversations, Byrd digitized and shared Eva’s Man. The film was streamed online in spring 2021 by “Another Screen,” a streaming project by the journal Another Gaze. See Another Screen, “[Silence] […] [Laughter],” https://www.another-screen.com/silence-laughter. See also: Carter Mathes, “Resonance/Dissonance: Black Feminist Intertextuality and Gayl Jones’s Eva’s Man,” unpublished paper delivered at the American Studies Association Annual Conference, 2018.

3 Of Eva’s Man, the novel, Rita Felski writes, “Jones crafts a nightmarish picture of being reduced to a sexual thing, of a world where nothing exists beyond the threat or reality of copulation…The various men of the novel blur into a depersonalized collage of grabbing hands, jeering voices, and erect penises, anonymous, interchangeable ciphers in the text’s endlessly superimposed scenarios of violence and violation” (127). Rita Felski, Uses of Literature (Oxford, UK: Wiley Publishing, 2008). See also: Colin Winnette, “Read This One: Namwali Serpell on Eva’s Man by Gayl Jones,” The Believer, October 19, 2019, https://believermag.com/logger/read-this-one-namwali-serpell-on-evas-man-by-gayl-jones/.

4 Claudia Springer interviewed Addison in the early 1980s and reports in her article that Addison composed some of the music herself. Music by Rhasaan Roland Kirk, Pharaoh Sanders, and Santana rounds out the rest of the film’s score. Claudia Springer, “Black Women Filmmakers,” Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, no. 29 (February 1984). https://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/onlinessays/JC29folder/BlackWomenFilmkrs.html.

5 Bernard Nicolas, email to the author, April 27, 2021.

6 Allyson Nadia Field, Jan-Christopher Horak, and Jacqueline Najuma Stewart, eds. L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema (Oakland: UC Press, 2015).

7 See: Elizabeth Binggeli, “The Unadapted: Warner Bros. Reads Zora Neale Hurston,” Cinema Journal 48.3 (Spring 2009): 1-15; Robert Nemiroff, ed. A Raisin in the Sun: The Unfilmed Original Screenplay, commentary by Spike Lee, introduction by Margaret B. Wilkerson (New York: Plume, 1992).

8 Alfreda Masters, email to the author, March 27, 2022.

9 Alison Nastasi and Julie Dash, “‘There’s a Movement Here’: Pioneering Director Julie Dash on the LA Rebellion, Black Lives Matter, and the New Generation of African-American Women in Film,” Flavorwire, October 21, 2015, https://www.flavorwire.com/543984/theres-a-movement-here-pioneering-director-julie-dash-on-the-la-rebellion-black-lives-matter-and-the-new-generation-of-african-american-women-in-film.

10 Letter from Julie Dash to Alice Walker, July 6, 1977, Box 7, Folder 7, Alice Walker Papers, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Julie Dash was interviewed by fellow filmmaker Barbara McCullough for an episode of The View, a UCLA student cable program. “Julie Dash on UCLA’s ‘The View’ (c. 1979),” UCLA Film & Television Archive. https://www.cinema.ucla.edu/la-rebellion/lar-interviews.

11 “UCLA-TV,” UCLA Daily Bruin, November 15, 1977, 4.

12 Allyson Nadia Field, “Gidget Meets Hondo,” UCLA Library Film and Television Archive, https://www.cinema.ucla.edu/la-rebellion/films/gidget-meets-hondo.

13 Bernard Nicolas, oral history by Jacqueline Najuma Stewart, Allyson Nadia Field, and Jan-Christopher Horak, June 17, 2010. Archive Research and Study Center, UCLA Film & Television Archive, University of California, Los Angeles.

14 Ibid.

15 Greg Braxton, “Wanted: Someone Who Understands, Appreciates Human Frailty,” Los Angeles Times, February 13, 1999.

16 Savannah is sometimes erroneously cited as having won an Academy Award. The film did screen for Academy jurors to consider, but it was not nominated. Addison was the director of dialogue for an Oscar-nominated animated short, Sound of Sunshine, Sound of Rain (1983).

17 Masters met Addison at UCLA in a course taught by Delia Salvi on directing actors. Salvi was, according to Masters, the UCLA professor whom Addison “most admired, respected and learned the most from.” Alfreda Masters, email to the author, March 27, 2022.

18 Alfreda Masters, phone conversation with the author, April 30, 2021. I was able to watch Savannah because Masters generously shared her copy with me.

19 Nina J. Easton, “The Invisible Women: In Hollywood’s rush to embrace black filmmakers, women directors are being left out, but some expect the picture to change,” Los Angeles Times, September 29, 1991.

20 Greg Braxton, “Television: Prime Time for a Show of Diversity,” Los Angeles Times, February 14, 1999.

21 Addison was close friends with EZ Streets director Paul Haggis who later dedicated his Oscar-winning film Crash (2004) to Addison. She had been one of the first to read the film’s screenplay. Tom Steadman, “Woman Left Impression on Director,” Greensboro News and Record, June 23, 2005.

22 There was at least one familiar face from Addison’s UCLA days on Knots Landing: Kent Masters King, Alfreda Masters’ daughter, had a recurring role on the show, and in 1991, Addison directed her in at least one episode.

23 Alan Carter, “Black by Popular Demand,” Emmy, vol. 19, no. 1 (Feb. 1997), 28.

24 On Angelou’s early cinematic work, see Hayley O’Malley, “All Day Long,” Black One Shot 16.3, ASAP/J, September 24, 2020, https://asapjournal.com/16-3-all-day-long-hayley-omalley/.

25 Braxton, “Human Frailty.”

26 Toni Morrison was one of Gayl Jones’ earliest and most ardent supporters, editing Corregidora (1975), Jones’ first novel, as well as Eva’s Man. See: Hilton Als, “Toni Morrison and the Ghosts in the House,” The New Yorker, October 19, 2003.

< Back to the Archive Blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation