After a 31-year career in film preservation, including almost 11 years at UCLA, Scott MacQueen has retired from his role as Head of Preservation at the UCLA Film & Television Archive. During his time at the Archive, MacQueen supervised the restoration and long-term preservation of nearly 100 films, many from the first half of the 20th century, including Hollywood studio classics and lesser-known independent works that were at risk of being lost.

In this interview, MacQueen shares career highlights, challenges, and what preservation means to him:

Tell us about your career trajectory.

Like so many people of my generation, I was exposed to classic cinema at a young age through television. All of the major studio films were being syndicated in the 1960s. Many of us saw Hitchcock, the Marx Brothers, and the Universal horror pictures when they first played on local television. The first network airing of The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) was all anyone talked about in school Monday morning. And with that, we still had the old movie palaces, rapidly vanishing as the shoebox theater took over the mall.

So I became enamored of film. I was a voracious reader, but the immediacy of movies appealed to me—moody camerawork, music, performance, eventually recognizing directorial control. I attended the film program at NYU, then worked as a production assistant and assistant director for 10 years, on commercials, music videos, low-budget features and some TV. I moved to Los Angeles in 1991 and wound up heading the restoration program at Disney for 10 years, followed by a job at PRO-TEK Vaults. In 2012, I was hired by the UCLA Film & Television Archive with the task of assessing the Laurel and Hardy nitrate materials, which led to my role as the head of the preservation department.

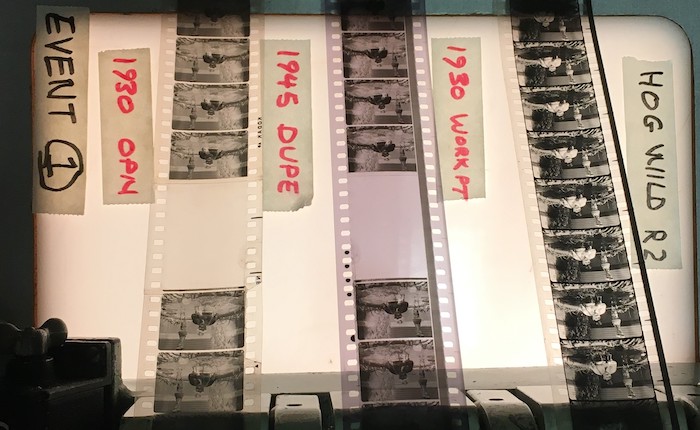

Comparing film elements for the restoration of Laurel and Hardy's Hog Wild (1930, above) and Sons of the Desert (1933, below).

What inspired you to become a film preservationist?

The real eye-opener was in the 1970s, when I began seeing 35mm prints of classics at The Museum of Modern Art and the Regency Theatre in New York, like The Docks of New York (1928), The Old Dark House (1932), The Thin Man (1934) and Mad Love (1935). I was impressed by how a newly struck 35mm print from a camera negative could look. Films that had been lost were also being rediscovered. I saw Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933) at the New York Film Festival, while in 10th grade, when the unique nitrate print was uncovered. I never dreamed that, 50 years later, I would be properly restoring it at the Archive.

Which preservation projects are you most proud of?

My greatest affection is for the Hollywood film, and Trouble in Paradise (1932) is my favorite Ernst Lubitsch film. Our work proceeded from the Paramount nitrate print, the best surviving copy. I’m very happy to have rescued the Delmer Daves noir The Red House (1947) using the camera negative—that’s a picture that suffered through terrible public domain copies. I’ve always loved The Lost Moment (1947), a Henry James story, and felt it an underrated film. Gun Crazy (1950), Men in War (1957), International House (1933) and Too Late for Tears (1947) are all superb films that resonate with me.

I’m very proud of Enamorada (1946), one of the masterpieces of Mexican cinema that we restored with The Film Foundation. El fantasma del convento (1934), a Mexican ghost film, was a discovery to me, an early example of the Catholic supernatural drama that has been a mainstay of Mexican cinema ever since.

35mm print used in the restoration of Trouble in Paradise (1932).

The Argentinian noirs brought to us by the Film Noir Foundation were also revelations: El vampiro negro (1953), Los tallos amargos (1956) and La bestia debe morir (1952). Argentinian cinema in the 1930s to ‘50s rivaled Hollywood for their quality and production value, sadly underappreciated today.

I’m very satisfied with these projects for their quality and what the films themselves represent.

Which preservation projects proved to be the most challenging?

The most challenging ones included The Drums of Jeopardy (1931) and White Zombie (1932). Both were independent, so-called “Poverty Row” productions, filmed cheaply. They were so popular in their day that the negatives wore out from overprinting, to wring out every last nickel, and there were no formal master positives to fall back on. They were in particularly bad condition.

The Drums of Jeopardy is a mystery thriller starring Warner Oland and produced by Tiffany Productions. It was pieced together from six different copies. We had two reels of camera negative, one reel of nitrate print from the Packard Humanities Institute collection, one reel of nitrate dupe print from the British Film Institute, and the other four reels had to come from three poorly made 16mm prints. Everything was chewed up. Piecing the movie together from the best surviving materials often became a shot-by-shot project.

That project rivaled White Zombie, the seminal zombie film starring Bela Lugosi, which also had multiple sources. Again, with all the damage, it was a matter of comparing them shot by shot, picking the best quality sections from each copy. If more funding had been available we would have done both projects digitally, further alleviating the nicks, tears and scratches.

Above: A damaged frame from an original 35mm print of White Zombie (1932).

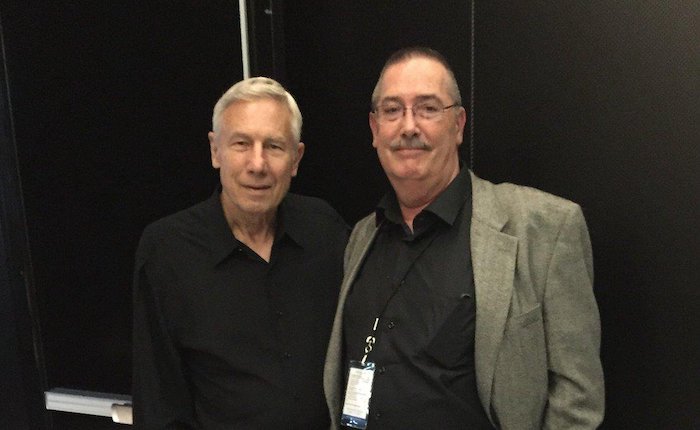

Below: Bela Lugosi Jr. and Scott MacQueen at the 2015 UCLA Festival of Preservation screening of White Zombie.

Depending on who you ask, you can sometimes get a different definition of “preservation.” How do you define preservation and what does it take for you to consider a film successfully preserved?

There are people who think that preservation is the mere fact that there is a print in the collection. My definition for preservation is the creation of a new preprint on a title, either a negative, a fine grain or color separations, something that is meant to keep the subject viable for a long duration. I don't yet consider digital files to be that—maybe someday they will have all the properties for long-term keeping. But they are too fragile and there is no robust storage media. Right now, polyester film remains the most reliable way.

You also get different definitions of “restoration.” Does it mean making the film look like it did on opening day in 1937—repeating every blemish and flaw that may have been there? I think that restoring means making as clean a copy as you can, undoing damage and faults in the material that take away from its plastic beauty or its narrative storytelling, but without manipulating the work for the sake of making it “pretty” and palatable to today’s consumers.

Sometimes it's not the image but content that is questionable. Films like the original A Farewell to Arms (1932) had two endings. Some films were recut by their directors (D.W. Griffith and Abel Gance are notorious for this) or other hands. Many of these films have been mutable over time.

How has the field of film preservation changed over the years?

Preservation used to be a simple, straightforward process: identify the best quality 35mm master, from that make a 35mm film sub-master, and you were done. The sound may or may not have been re-recorded; it certainly was never electronically cleaned.

Today, the state of the art in preservation demands digital picture work to erase embedded dirt, tears and scratches. Older optical soundtracks can exhibit camera noise, extraneous ambient noise and poor mixing. I don’t think that helps to tell the story and isn't respectful of the art, so we do digital sound work to clean it up. With Laurel and Hardy’s Oscar-winning The Music Box (1932), for example, I located the original nitrate pre-mix recordings, and by cleaning these and re-creating the original mix we were able to provide a restored track of a quality that has never been heard with such clarity in the film's 90-year arc.

Damaged 35mm film.

What about the kinds of films that are being preserved? Do you think that has also changed?

Yes, many more independent feature and short films are being preserved. That's a very good and necessary thing because these are the films that are most likely to be lost in the future. Digital filmmaking has been a great egalitarian tool, but I believe we will see tremendous losses over time. Today’s independent filmmaker is most at risk because they are working in the most fragile of media—digital media—and often lack the insight and resources to preserve their work.

What skills have proven essential throughout your career as a preservationist?

First would be a knowledge of classic cinema history and content, and a genuine fondness for it. Next, knowing what makes film work mechanically, how it has traditionally been put together, how you print, handle, operate and preserve film. The differences between 16mm, 35mm, print and fine grain, the history of amateur film markets. A broad perspective about allied and tangential arts and the difficulties faced in paper, painting and other media conservation. A sense of history. Finally, experience with project management and schedules.

How do you feel about the future of film preservation?

There's a mountain of material that begs to be copied. It will never happen, as you can’t save everything. But at the same time, it is important to save even what some would consider “junk.” Mamba (1930), for example, is a pretty lousy movie. But it was an independent, $500,000 production in two-color Technicolor, about a vile white plantation owner in east Africa who violently mistreats his workers and women of all colors. In the narrative he is depicted as a threat to the other European colonizers for diminishing the “White Man’s Prestige.” Such attitudes were taken for granted a century ago. We shouldn’t celebrate them or pretend that Mamba is a classic, but we need to confront the past to understand how we got to where we are.

Above: two-color Technicolor print used in the restoration of Mamba (1930).

Below: a scene from Dirty Gertie from Harlem U.S.A. (1946).

Toss the coin to tails, the Archive recently preserved Dirty Gertie from Harlem U.S.A. (1946). It's an all-Black-cast retelling of Somerset Maugham’s short story “Rain” by a Black director, Spencer Williams. It was done for a buck and a half and probably shot in four days, but it's indicative of the kind of entertainment supplied to all-Black theaters in the 1940s. And it's an attempt by Black filmmakers for Black ownership.

Finally, there’s nothing about film preservation that a large influx of money would not help. That has been the one constant over the last half-century. In addition to funding, I hope to see a richer spirit of collaboration and sharing of resources in the field. By and large, UCLA has had splendid cooperation with our partner institutions and hope that we may continue to build on those relationships.

—edited by Jennifer Rhee, Digital Content Manager

< Back to the Archive Blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation