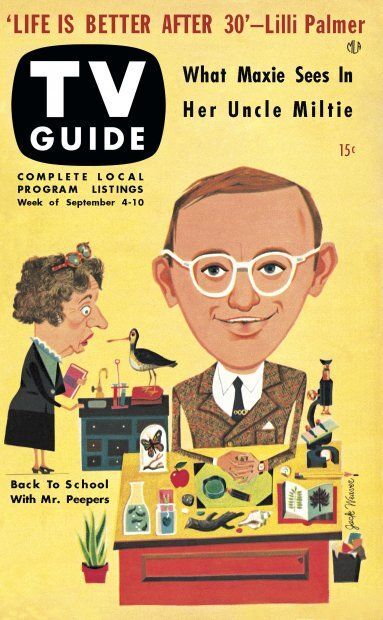

Wally Cox as Mr. Peepers

Our guest writer is Dwight Swanson, who for almost 20 years has advocated for the preservation and promotion of home movies as a co-creator of Home Movie Day and a founding board member of the Center for Home Movies (CHM). In addition to spearheading the Home Movie Archive Database and the Home Movie Registry on the CHM website, his work includes Amateur Night: Home Movies from American Archives, Home Grown Movies, and an amazing worldwide 24-hour home movie event with films shown from around the world. This blog was made possible by the Myra Reinhard Family Foundation.

People who are interested in knowing what it was like in the 1950s when American families regularly watched their home movies mostly have to rely on hearing stories of dads (usually dads, but sometimes moms) setting up projectors in their living rooms and pulling out reels of vacations, holidays and birthday parties. The September 27, 1953 episode of the sitcom Mister Peepers, however, centers around a home movie reel that Peepers’ best friend, Mr. Weskit, shot while on vacation, and is one of the few early television shows to depict the experience of making and showing home movies. It gives us modern viewers a sense of what people thought of watching home movies at the time—in short, they thought they were terrible.

Broadcast live and shot on stage before an audience in New York City, Mister Peepers began as a Thursday evening summer replacement series in July 1952 on NBC. The show was only intended to air for a few months. However, Doc Corkle, the sitcom that was to fill NBC’s Sunday evening slot in the 1952-53 season, was canceled after a mere three weeks, and Mister Peepers was resurrected and returned for three seasons. The show featured the titular Robinson Peepers, a mild-mannered new science teacher at Jefferson City Jr. High in a small Midwestern city. It was a vehicle for Wally Cox, an unassuming but singular performer who uncomfortably entered into show business after he had begun to perform monologues and sketches while working as a silversmith in New York City, where he was roommates with his childhood friend Marlon Brando. The other main character in the home movie episode was Tony Randall, who played the affable but know-it-all history teacher Harvey “Wes” Weskit.

Broadcast live and shot on stage before an audience in New York City, Mister Peepers began as a Thursday evening summer replacement series in July 1952 on NBC. The show was only intended to air for a few months. However, Doc Corkle, the sitcom that was to fill NBC’s Sunday evening slot in the 1952-53 season, was canceled after a mere three weeks, and Mister Peepers was resurrected and returned for three seasons. The show featured the titular Robinson Peepers, a mild-mannered new science teacher at Jefferson City Jr. High in a small Midwestern city. It was a vehicle for Wally Cox, an unassuming but singular performer who uncomfortably entered into show business after he had begun to perform monologues and sketches while working as a silversmith in New York City, where he was roommates with his childhood friend Marlon Brando. The other main character in the home movie episode was Tony Randall, who played the affable but know-it-all history teacher Harvey “Wes” Weskit.

From our 21st-century perspective, the show has a refreshingly simple, low-budget theatrical style, with a three-act structure interrupted by live commercials for Reynolds Aluminum. It was largely unseen for decades because, unlike other 1950s shows such as I Love Lucy or the stylistically similar The Honeymooners, Peepers was not shot on film. It was not available for the syndication market because of the lesser quality of the 16mm kinescopes that were the only existing versions of the show. It was not until the copies held by the UCLA Film & Television Archive of the first two seasons were released as DVD sets that the show became accessible again for modern audiences.

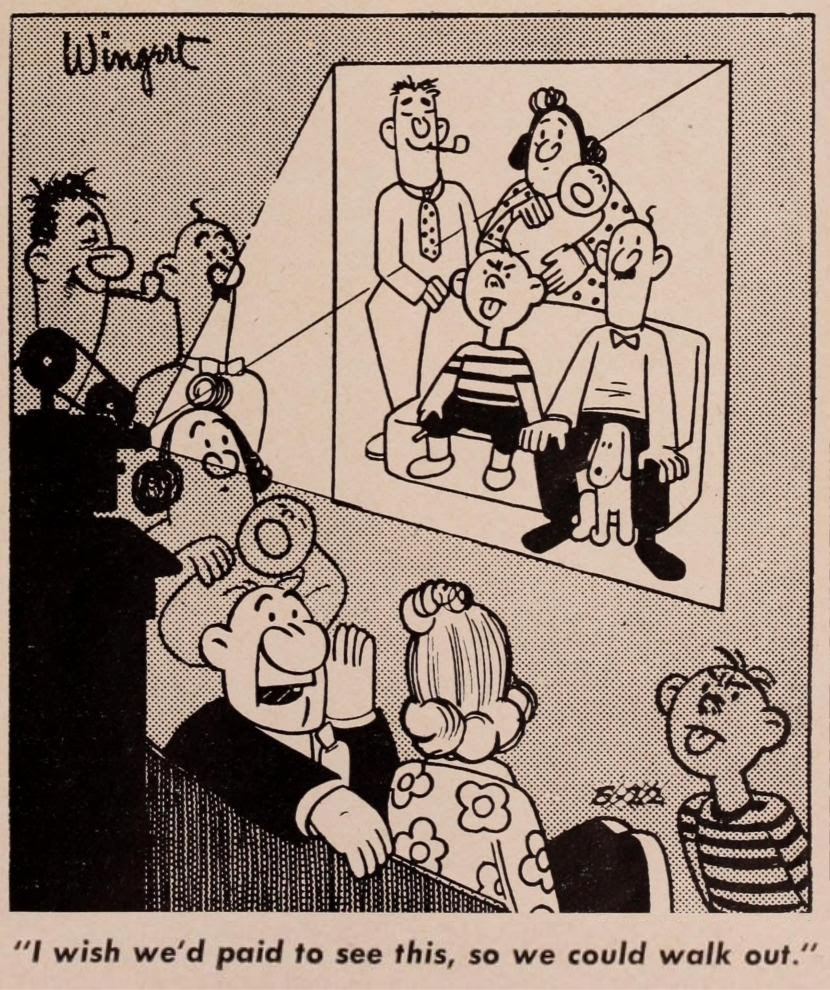

Two earlier examples of watching home movies on film or television in UCLA’s collection—the short film Home Movies (1940) by comedian Robert Benchley and a 1952 episode of The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show—also play up the comic aspects of home movies, showing them as an experience to be endured by long-suffering friends and neighbors.

In Home Movies, Benchley shows a home movie of a vacation to several unenthusiastic friends following a dinner party. The reel ends up being a string of filmmaking errors (out-of-focus shots, inadvertent slow-motion, baffling compositions, etc.), narrated by an unapologetic Benchley. By the end of the screening, only one yawning audience member remains, the rest having snuck out in the dark. The “Vanderlip’s Party” episode of the Burns and Allen show centers around the dread that George Burns and his friend Harry Morton go through in anticipation of seeing his friend Chester Vanderlip’s home movies yet again, going so far as to plan on taking sleeping pills so they could doze through the screening. George claims to have seen the same movies 35 times in five years. “I had more fun listening to my barber and watching a hot towel on my face,” he says, “Now don’t get me wrong, I think showing home movies of your family at home is fine if you’re the Barrymore family.”

There are a few other later examples of home movies on television in the UCLA archive. Your Funny, Funny Films was a short-lived precursor to America’s Funniest Home Videos that ran in the summer of 1963 and showed comedic real home movie clips from the public. A 1970 episode of The Bill Cosby Show (“Anytime You’re Ready, C.K.”) shows Coach Chet Kincaid borrowing a camera to film football practice, but then putting it to use to make his own homemade comic films. Finally, “The One with the Prom Video” (1996) episode of Friends ends with a home video of Monica and Rachel’s prom night as a vehicle for revealing a backstory in Ross and Rachel’s relationship.

Marion Lorne as Mrs. Gurney and Wally Cox as Mr. Peepers

The Mister Peepers home movie episode, though, is the most thorough look at home movie making and viewing. The story begins in the school’s men’s room where Peepers is washing up. Wes enters excitedly and tells Peepers that after waiting three weeks to get the home movies of his vacation developed, he had received a postcard from the camera store that his film was ready to be picked up. Overflowing with excitement, Wes tells Peepers that these were the first movies that he ever took, and he “followed the instructions right to the letter. They should be perfect.” Wes is nearly bursting with anticipation at seeing them, and he tries to prepare Peepers for the cinematic techniques that he borrowed from classic Hollywood films. “You’re familiar with the sweep, the movement of Gone with the Wind?” he asks, “And the brilliant composition and sustained action of Ben Hur?” He describes his personal filmmaking style (ridiculously and pompously, since he has just shot his first-ever reel) as “making the camera a person… when you look at those pictures it will be just the same as if they were being seen by a person.”

Tony Randall as Mr. Weskit

Despite his grand ambitions, Wes’ film ends up being a mixture of mundane scenes typical of home movies such as him petting a dog, posing shirtless while flexing his muscles, two separate shots of “damp grass,” a barely visible plane in flight, which Wes says he “borrowed from the aviation classic Wings,” and a funny running gag involving a mysterious stranger. Mostly, though, just as in Robert Benchley’s film, the reel is a litany of filmmaking mistakes, including cut off heads, unsteady pans, pointing the camera at his shoes, leaving the camera running while it is on a picnic blanket, a “character study” that only shows an empty bench, and the film running out before a climactic shot of a waterfall. All of the scenes are ridiculous but not completely unrealistic versions of shots that can be found in actual home movies, even though it is hard to tell what they did on their trip.

Following the screening, Peepers, always the supportive friend, tells Wes sincerely that the film was “really swell” and then in the show’s coda tells us (the audience) that he looks forward to making home movies himself someday. That may have been meant as a threat then, but now that the ritual of watching home movies on film is long over, the thought of an evening of Mr. Peepers’ home movies sounds awfully fun, honestly, because nostalgia and the aura of wistfulness brought about by the technological obsolescence of film has—mostly, at least—turned watching old home movies into a rousing evening of entertainment.

This episode is now available on the Archive's YouTube channel:

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation