Old Boyfriends

On the occasion of a new 35mm print of Joan Tewkesbury’s directorial debut, Old Boyfriends (1979), now in circulation, UCLA Film & Television Archive Programmer KJ Relth and Maya Montañez Smukler, who runs the Archive Research & Study Center, talk about films directed by women in the 1970s and their current revitalization in theaters, on streaming platforms and DVD/Blu-ray.

MAYA MONTAÑEZ SMUKLER: At the beginning of the year, together we programmed the Liberating Hollywood series—based on my new book Liberating Hollywood: Women Directors & the Feminist Reform of 1970s American Cinema. One of my book’s main arguments is that the leading mythology of that era was that anyone who was young, ambitious and loved film could make a movie. This was true, but mostly for white men. However, at the same time, second-wave feminism was challenging and changing every part of American society, politics and culture, and for the first time since the silent era the number of women directors making feature films, in and around Hollywood, began to increase. By my count there were 16 women—all white women—who directed (sometimes writing/producing and even starring in) at least one narrative feature between 1966-1980. A small number compared to their male peers, but much larger than the singular eras of Dorothy Arzner and Ida Lupino during the previous 40 years. All together, these filmmakers, during the 1970s, produced about 25 films. We could schedule only about 14 films, so our first challenge was deciding what to show!

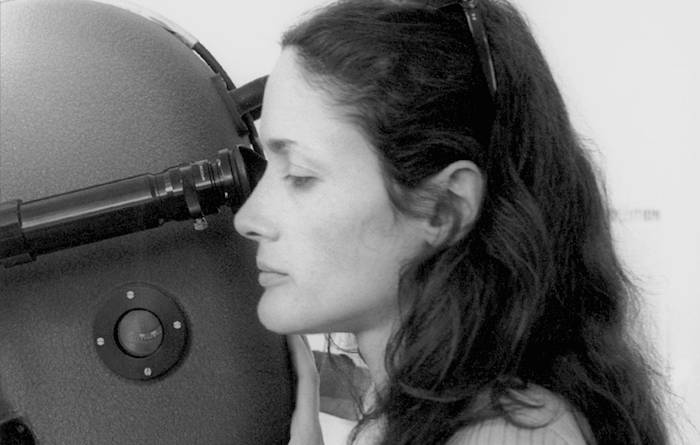

Filmmaker Stephanie Rothman (Terminal Island, The Velvet Vampire)

KJ RELTH: When we were in the brainstorming phase back in April 2018, you and I went through your book, filmmaker by filmmaker, and tried to narrow their filmic output down to a somewhat strategic lineup, highlighting films we knew had not been shown theatrically in Los Angeles in a number of years; in some cases, we opted for titles that had not screened since their original releases over 40 years ago. Once we realized that we wanted each night to focus on a single filmmaker, we had to make some tough choices. Ultimately, we focused on filmmakers for whom we could find the best, most viable screening materials.

SMUKLER: And this is where we had some moments of existential crisis. Some of the prints you found—the only ones you could find, after months of searching—were badly faded and scratched. We were faced with the dilemma of showing a deteriorated print of a film that hadn’t been seen in years, or not showing that print because of its poor condition and then continuing to keep the film from being seen. We realized pretty quickly that a conversation about the condition of these prints—and the state of women filmmakers in archives—was going to be part of the series. It’s not only that films made in the 1970s are 40-50 years old and need to be preserved and in many cases restored, but the women who made movies during this era are already precariously situated in history, and as a result their status in archives is equally at risk.

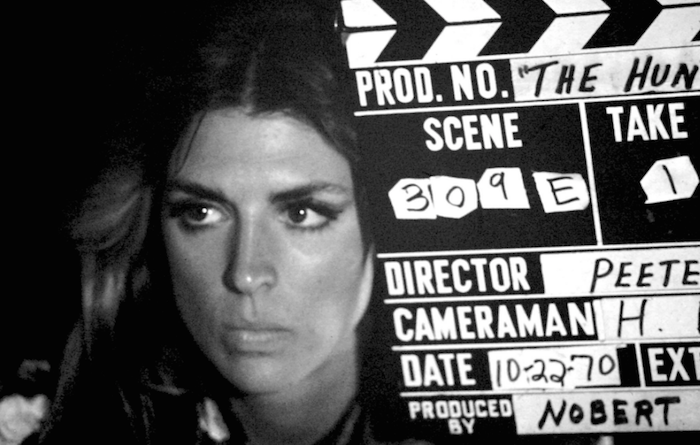

Filming of Bury Me an Angel by Barbara Peeters

RELTH: As a film programmer, it feels like a biological imperative to champion the work of women, especially work that was initially, for myriad reasons, neglected upon its original release. It is so important to reject traditional film histories, or at least offer a corrective, especially when those histories are now understood to be sexist, racist and exclusionary. As an archive, we collectively put special emphasis on exhibiting the rare and the underscreened. While of course our preference would be to show each of these films as newly preserved 35mm prints, budgetary restraints made this goal impossible. So we had to work with the understanding that we would screen prints if they were viable, even if they were badly faded or scratched.

We both had our favorites from each of these 16 filmmakers, and one title that we thought fit perfectly into the program was the rarely-screened Chilly Scenes of Winter (a.k.a. Head Over Heels, 1979) by Joan Micklin Silver. I reached out to IFC Center in New York, who had screened the film in 35mm as recently as 2016. When I contacted the print source, they claimed that they no longer had that 35mm print. I contacted all the private collectors to whom I have direct lines, and even bothered some local celluloid sleuths and emailed the dedicated, international film programming listserv, but that seemingly single remaining 35mm print never manifested. Serendipitously, Cohen Media Group had been planning a new 2K digital restoration of Micklin Silver’s earlier ensemble piece, Between the Lines (1977)—also a super rare title because the 35mm elements were badly in need of restoration. Film stock from the 1970s and early 1980s has a tendency to lose its color over time, resulting in a pink or red-tinted image. Cohen completed the restoration project just in time for the Liberating Hollywood series, so we paired Between the Lines with a later film by Micklin Silver, Crossing Delancey (1988), for the closing night double bill, a print that was easily accessible through Warner Bros.

Crossing Delancey by Joan Micklin Silver

We are also incredibly lucky that the Academy Film Archive puts an emphasis on the preservation of works by filmmakers that might not have received the same accolades as their peers, but are vital to the legacy of American cinema. Just prior to our series, the Academy struck a brand-new 35mm print of Stephanie Rothman’s The Velvet Vampire (1971), so we were able to make use of that and proudly invite Ms. Rothman to join us. The Museum of Modern Art in New York is also in the process of restoring three of Ms. Rothman’s films, including Terminal Island (1973), an effort spearheaded by curator Anne Morra.

And then, there’s Joan Tewkesbury’s Old Boyfriends. Maya, why would you say this title was such a vital one for the opening night of our series?

SMUKLER: Joan Tewkesbury’s directorial debut Old Boyfriends—written by Paul and Leonard Schrader—is something you can find on VHS or in a crummy version on YouTube, but it rarely if ever screens at repertory theaters and, as of yet, hasn’t had a DVD or Blu-ray release. It’s also a perfect late-’70s film. Starring Talia Shire in her first leading role after playing some of the decade’s most iconic supporting characters, this movie fits in the “New Woman Film” genre, which was popular at the time in how it explores themes of “women’s lib.” But it tweaks the genre. Shire’s character is suffering a nervous breakdown of sorts and her journey to find her old boyfriends is surprising.

Maya Montañez Smukler and Joan Tewkesbury (watch the Q&A)

It was double-featured with Thieves Like Us—directed by Robert Altman and written by Joan—and Joan was in attendance for a lively Q&A. The print of Old Boyfriends was so red and faded, something we had known before and warned the audience and Joan of. In a way it felt like a bonding experience to watch the movie with that crowd at the Billy Wilder Theater, the director and producers—Ed and Annie Pressman—in attendance. Joan hadn’t seen the film since she made it and I’m not sure the Pressmans had either! It sounds dramatic, but together we witnessed the deterioration of a film and in the context of the series, the vulnerability of these women filmmakers’ legacies.

RELTH: Once we knew that we wanted Old Boyfriends to be the series’ kick-off film, we did everything we could to find the best print possible. There are three known 35mm prints in the U.S., and all of them had faded to red, some worse than others. We borrowed all three from two different archives so that our superhero projectionist, Jim Smith, could take a look at each side-by-side and determine which would be the best to play.

At the same time that we were going to print with the series lineup, the film’s distributor, Rialto Pictures, discovered an original negative of Old Boyfriends, in tact and with color timing information. As a result of the combined efforts of the Archive, Joan, the Pressmans and Rialto, the company struck a new 35mm print. While this print was not ready in time for our series, it is now finally available for theatrical booking and streaming on Kanopy as a digital scan of the new 35mm elements!

Moment by Moment by Jane Wagner

SMUKLER: Another film that was a must for us to show was Moment by Moment (1977), written and directed by Jane Wagner, starring Lily Tomlin and John Travolta and produced by Robert Stigwood. Tomlin and Travolta play lovers—she’s a rich Beverly Hills divorcée and he’s a young street hustler. It was a risky project for everyone involved: Travolta was a phenomena with the recent success of Saturday Night Fever and Grease; both actors were celebrated for their comedic chops; Wagner was a first-time film director helming a studio picture. Together, they were trying something different: a very romantic melodrama featuring two enormous movie stars who spend the entire film talking about their feelings while holed up in a Malibu beach house. The critics ripped the film to pieces.

We were curious about the state of the 35mm print that came from Universal and what kind of audience would show up. Both were wonderful! There is much to love about this movie, which has become a bit of a cult/camp classic. The buzz post-screening was sort of euphoric, everyone was surprised at how sweet, romantic and life-affirming the movie was and how dazzling the actors were considering how it suffered during its initial release. I think we all left the theater feeling a little sun-kissed and in love!

Testament by Lynne Littman

RELTH: Yet another film that was essential for this series was Lynne Littman’s Testament (1983), which, due to its Academy Award-nominated performance from the dynamic Jane Alexander, can be found at the Academy Film Archive in Hollywood. Lynne was one of the “Original Six,” a septet of women members of the Directors Guild who came together in 1979 to fight for equal representation in the film industry. Lynne is a firecracker personality, super candid and forthcoming about her four-decade career as a filmmaker (mostly of documentaries), and happens to live here in Los Angeles, so we were overjoyed to have her at the Wilder to share this film with so many who had never seen it before. Testament, her only narrative feature effort, was somewhat overshadowed in its day due to the almost simultaneous release of The Day After (Nicholas Meyer, 1983) on American television. Lynne’s film was originally produced for American Playhouse and was given a theatrical release thanks to Paramount Pictures. Her short documentary, Number Our Days (1975), about a group of retired Jewish folks living in Venice, CA, won an Oscar for Best Documentary Short Subject, making Lynne one of the most celebrated and lauded filmmakers in this series—who, somehow, shockingly, is still not a household name.

SMUKLER: The series was intended as a celebration of this “generation” of 1970s women directors and the variety of films they made, and it in turn became part of the rallying cry to preserve these movies and the legacy of their makers. We’re still in search of a better print or elements that could lead to the restoration of Barbara Peeters’ classic feminist biker film Bury Me an Angel (1971), which we screened a very scratched print of; and hoping to find anything on Karen Arthur’s first feature, Legacy (1974). Taking inspiration from Talia Shire’s determination to find her old boyfriends, I believe a print is out there, somewhere!

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation