Until the early 1950s, all movies were made with cellulose nitrate-based film stock, which is inherently unstable and highly flammable, prone to rapid decomposition if not properly conserved. Finding a nitrate film that is safe to project is a challenge, which has made seeing nitrate on the big screen an exceedingly rare experience. Ahead of our July 27, 2018 nitrate screening of William Wyler's Counsellor at Law (1933), we asked former Head of Collections Rosa Gaiarsa: what is the process of getting a nitrate film from the vault to the screen?

Rosa Gaiarsa: Before any nitrate film makes it to the big screen, it has to go through a very detailed condition assessment. First of all, the film is checked for nitrate deterioration, which may occur for many reasons: the natural aging process, poor manufacturing or processing of the film stock (especially during WWII), inadequate storage conditions in the past, and/or adverse chemical reactions to others materials, like film cement, splicing tape or even other film stocks. If there is significant nitrate deterioration, the film cannot be projected.

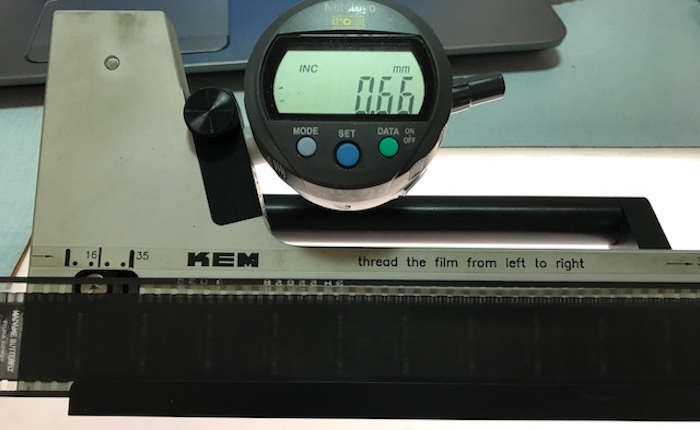

Measuring film shrinkage

The second most important thing to check is shrinkage level. All nitrate film shrinks with age, and unfortunately the degree of shrinkage increases when the film is stored under low temperature and humidity, which is necessary to prevent deterioration and keep it safe from ignition. The older the film, the more shrunken it becomes—it’s unavoidable. If the film is too shrunken it cannot run through a projector, which pulls the film by the perforations on the sides of the film. On shrunken film the distance between the perforations is too short, and running it through the projector would shred it to pieces.

Next, nitrate film has to be checked for physical integrity: is it complete or missing any scenes? Does it have too many splices made to repair previous breaks during projection? Are the perforations damaged?

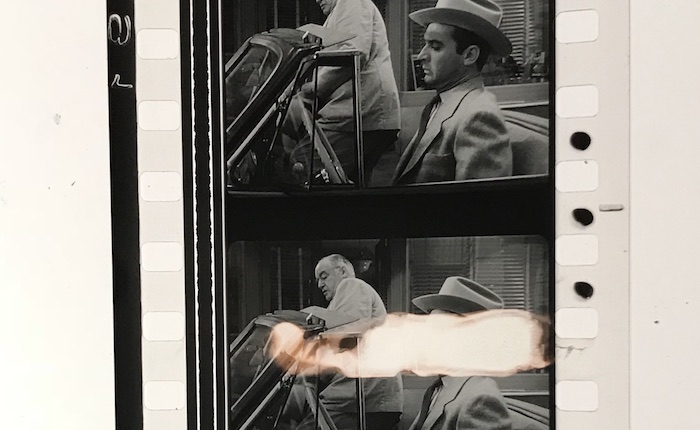

Nitrate deterioration from a cement splice

Nitrate deterioration from a cement splice

Passing these tests for deterioration, shrinkage and physical integrity, the film is finally prepared for exhibition. Every foot of film must be carefully inspected, and the average feature film is 10,000 feet long. Every splice has to be checked, reinforced or remade if necessary. Every broken perforation has to be fixed with the proper repair tape. The countdown and tail leaders also have to be checked to assure a smooth transition between reels. The process of prepping a nitrate film takes two to three times longer than prepping an acetate film, but it is absolutely necessary to ensure safety when screening a film that is inherently dangerous due to its flammability.

Nitrate print of Counsellor at Law (1933) from the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Photos courtesy of Staci Hogsett.

< Back to the Archive Blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation