Night Tide (dir. Curtis Harrington, 1961)

I’ve just finished reading Henning Engelke’s massive tome, Metaphern einer anderen Filmgeschichte. Amerikanischer Experimentalfilm, 1940-1960, which is certainly the most important work I’ve read about American avant-garde cinema in the last few years. Unfortunately, only available in German, one can only hope that an English-language press will pick up this voluminous (575 pages), illuminating and groundbreaking work.

The dominant, “essential cinema” canon of post-World War II American experimental film, as established by Jonas Mekas and P. Adams Sitney, was contextualized as running parallel to Abstract Expressionism as a modernist fine art movement, and featuring the aesthetics of an exclusive cadre of filmmakers that privileged non-narrative forms and unconventional formal devices, subjectivity and the personal point of view of its practitioners. Engelke modifies and expands this historical discourse by demonstrating the often free-floating borders between aesthetic modernism, technology (16mm/computers), information theory, contemporary psychological theories of perception, and postmodernism. In doing so, he not only recuperates many experimental films and filmmakers who also worked in the allied fields of industrial/educational films and information science, but also opens our view to geographies of production and reception beyond New York, most importantly San Francisco.

Divided into 10 chapters, including an introduction and a conclusion, Engelke proceeds roughly chronologically, although there are numerous overlaps. Chapter 2: “The Crisis in Representation,” theorizes that World War II, the dropping of the atomic bomb and the simultaneous emphasis on film propaganda produced a backlash against the supposed objectivity of the image. Instead, the writings of Maya Deren, Helen Levitt’s In the Street, and Rudy Burkhardt’s films called for the inscription of the technological apparatus in cinema, acknowledging not only human subjectivity, but also the machine character of cinema production.

Chapter 3: “Experimental Film and Film History” begins with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s “Art in Cinema” program of the late-1940s, then discusses three versions of experimental film history and ends with the influence of László Moholy-Nagy’s Vision in Motion (1947) on subsequent production. The latter’s emphasis on abstraction carries over to Chapter 4: “Metaphors of Visual Music,” which perceives light itself as a metaphor for truth to connect BeBop Jazz, and Kandinsky with films as diverse as the Whitney Brothers’ Five Film Exercises (1943-44), Sara Arledge’s Introspection (1947), Dorsey Alexander’s Life and Death of a Sphere (1948), Jordan Belson’s Mandala (1953), Harry Smith’s films, and the notion of expanded cinema. Chapter 5: “Romantic Poets? Experimental Film Organizations” looks at reception, distribution and the internecine warfare between Amos Vogel’s Cinema 16, Maya Deren’s Creative Film Foundation, Jonas Mekas’ Film Culture, and other initiatives.

In Chapter 6: “Phantasmagoria, History and ‘the Closed Field,’” Engelke explores the hazy border between psychology and spiritualism in Gregory Markopoulos’ Psyche (1947), Robert Vickrey’s Texture of Decay (1951), Francis Lee’s 1941 (1941), Parker Tyler’s book, The Hollywood Hallucination, and the films of Willard Maas, Marie Menken, Ian Hugo, Charles Kessler, Kenneth Anger, and Curtis Harrington. All these examples belie connections to Abstract Expressionism. Rather, their arbitrary referents and self-reflexive formal devices, often in search of a gay identity, can be understood in terms of the metaphor of a “closed field,” a term also associated with cybernetics and information theory.

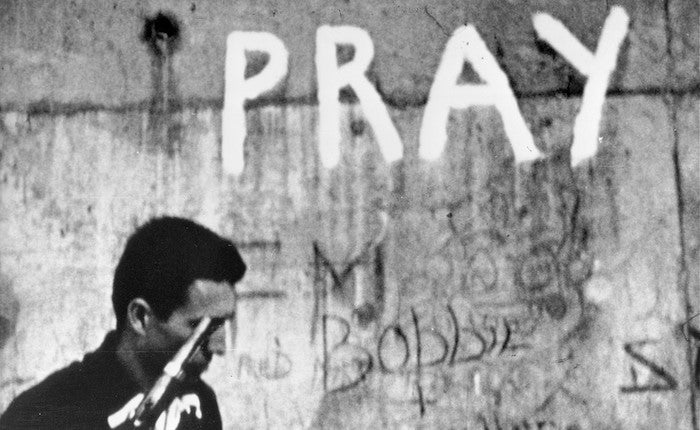

Chapter 7: “Recursive Visions – Experimental Film and Cybernetics in San Francisco,” then, analyzes the cybernetics-inspired educational films of Gregory Bateson and Weldon Kees, like Hand-Mouth Coordination (1951), which inscribe both camera technology and the subjectivity of the observer in a self-reflexive system, before drawing parallels to Sidney Peterson’s Workshop 20 films, like The Cage (1947), and other San Francisco filmmakers, e.g. James Broughton and Frank Stauffacher. Focusing on Christopher Maclaine’s The End (1953), Jordon Belson’s Vortex Concerts, Bruce Conner and Wallace Berman, Chapter 8: “The Politics and Aesthetics of Eliminating the Parameters of the Cinematic” theorizes the elimination of a controlling artistic persona in favor of an audience’s ability to generate a multiplicity of perspectives, encouraged through the use of disjointed editing and multiple exposures.

The End (dir. Christopher Maclaine, 1953)

Anticipation of the Night (dir. Stan Brakhage, 1958)

Finally, Chapter 9: “Metaphors on Vision,” explicitly deflates Jonas Mekas and P. Adams Sitney’s vision of the romantic experimental filmmaker by reading Stan Brakhage in terms of a vision liberated from logocentrism and returning to a romantic, pre-modern, ur-perception that has much in common with the theories of non-verbal communication formulated by Bateson and Kees.

If all this sounds extremely dense, it is, and my efforts at describing Engelke’s historical narrative will necessarily fall short, given the brevity of this blog. He concludes: “In this book I have attempted to juxtapose a one-sided modernist perspective to a diverse image which connects contemporary contexts and points to underlying continuities, while denying a unified meditation in terms of avant-garde, classic modernism, or postmodernism” (p. 504). Indeed, Engelke offers consistent and eye-opening surprises in his conceptual juxtapositions, while returning to film history a significant number of experimental filmmakers who had been eliminated from the pre-1960s canon of avant-garde cinema.

< Back to the Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation