Losing Ground (1982)

A couple of weeks ago, the Billy Wilder Theater presented our slightly abridged version of Tell It Like It Is: Black Independents in New York, 1968-1986, the film series curated by Michelle Materre and Jake Perlin and first presented by the Film Society of Lincoln Center. The Archive’s Head of public programs Shannon Kelley chose to open with Losing Ground (1982), Kathleen Collins’ remarkable debut feature, which is now experiencing its first theatrical release through Milestone Films, 33 years after its premiere. It is one of the first fictional feature films directed by an African American woman, as filmmaker Julie Dash emphasized in her post-screening discussion, while her own masterpiece, Daughters of the Dust (1991), is the first fiction feature film directed by an African American woman to receive general theatrical release in the U.S. Furthermore, Shannon Kelley notes, Losing Ground has been virtually unseen, since Kathleen Collins’ tragic early death from cancer in 1988 at the age of 46.

In fact, the film was for all practical purposes lost, until Collins’ daughter, Nina, found the camera negatives, and with the encouragement of Professor Terri Francis from the University of Indiana, Bloomington, she had DuArt digitize them. However, the track negative yielded terrible sound, so Dennis Doros and Amy Heller of Milestone had the track rerecorded and cleaned, although sound restoration of the synch problems in the film’s opening scene and other issues await the day the original mag tracks are found. Not surprisingly, then, I had only heard about Losing Ground, and so I was unprepared for a film of such maturity and visual acuity that it took my breath away. As in the case of the L.A. Rebellion, its reception was much more positive in Europe where the film played at festivals in Portugal, Munich, Berlin and London. What had happened?

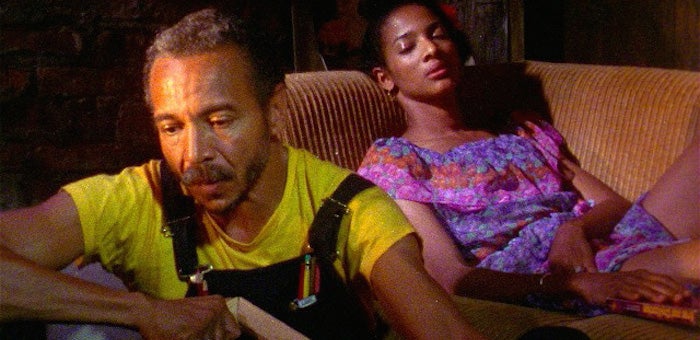

Bill Gunn and Seret Scott in Losing Ground (1982).

When Collins finished her film, financed through foundation grants and many small donations, it seems audiences in this country were not prepared for a sophisticated comedy of manners, situated among the black middle class and intellectual elite. It was the beginning of the Reagan era. Blaxploitation had lost steam by the mid-1970s and, anyway, that Hollywood version of African American life featured pimps, drug addicts, ho’s – all stereotypes and genre posturing. After that, African Americans virtually disappeared from theatrical screens altogether, remaining invisible until Spike Lee’s breakthrough, She’s Gotta Have It (1986), showing on August 8th in our series. When Collins tried to find a distributor for her film, she was met with cold indifference from producers, distributors and critics, many of whom were unable to see beyond the usual racist stereotypes depicted by Hollywood. It had a single screening at MoMA in 1983, then disappeared except for a WNET broadcast in 1987. Had the film been in French with Eric Rohmer’s name on it (Collins acknowledged his influence), the critics would have loved it.

Kathleen Collins. Image courtesy of Milestone Films.

Collins had graduated from Skidmore College and later attended the Sorbonne on a John Hay Whitney scholarship, where she did doctoral work on André Breton. As Peggy Dammond Preacely, an activist and childhood friend of Collins (her poem, “My Sister, My Friend” pays tribute to Collins), noted in her introductory remarks to the film, Collins joined the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), working on voter registration drives in the deep South. In the late-1960s, she became a professor of film history and screenwriting at The City University of New York, where she worked with Ronald Gray, who edited and shot her two films. Collins was also, as Julie Dash noted, a mentor to countless students and colleagues, and was considered a guiding light of the New York black independent film movement.

Peggy Dammond Preacely (left) and Kathleen Collins (center) participating in the

Peggy Dammond Preacely (left) and Kathleen Collins (center) participating in the

Albany, Georgia Freedom Movement in 1962. Image courtesy of Peggy Dammond Preacely.

Set in New York, the film opens with Sarah (Seret Scott) teaching a philosophy class to bored college students, immediately identifying her as a beautiful and extremely intelligent woman, not immune to students making passes at her. Her current research concerns the nature of ecstasy in art, and throughout the film we hear passages from her essay. Her husband Victor (Bill Gunn), meanwhile, is a painter whose work has just been acquired by a major museum; he pushes for the power couple to move upstate for the summer, even though she needs a library for her research. There is more trouble: he is a philanderer who needs constant reinforcement of his manhood, while she feels he is not attentive to her needs. Then, there is the giant shadow of her mother, a former stage actress, weighing on Sarah’s psyche. When an infatuated film student asks her to appear in his film, she refuses, then agrees, possibly out of spite for her husband, and soon becomes enamored with her co-star, a professional actor (Duane Jones).

Often screamingly funny, Collins layers her seemingly simple narrative. First, she rigorously controls her use of color, costumes and sets to indicate moods. Secondly, her heroine’s interventions concerning the nature of art and emotion catalyze thoughts about her relationships. Thirdly, by using a film within a film structure (it’s the “Frankie and Johnny” theme), she comments on the characters through music and dance. Without ever overtly addressing politics per se, Collins understands that African American women are doubly oppressed, both as minorities and as women. Sarah's intellectual confidence and verbal acuity stand in contrast to her husband’s intuitive and emotional grasp of art and reality, their unresolved conflicts functions of race and gender. Collins refuses to resolve the issues, leaving Sarah to ponder her fate between two men. As Collins noted in an interview: “While I’m interested in external reality, I am much more concerned with how people resolve their inner dilemma in the face of external reality.” I can think of few films as emotionally or intellectually dense. Go see it!

Watch a trailer for Losing Ground (1982):

Watch Peggy Dammond Preacely's introduction and Julie Dash's Q&A on July 18, 2015:

This retrospective screens at the Billy Wilder Theater from July 18 - August 23, 2015. Learn more >

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation