As part of the "Celebrating Orphan Films" series on May 13 and 14, 2011 at the Billy Wilder Theater, the UCLA Film & Television Archive will screen a trio of unique 1960s-era UCLA student films: Kinky (ca. 1966), Patient 411 (ca. 1965) and Five Situations for Camera, Recorder and People (ca. 1965). The original production crew for the latter two of these films included then-UCLA film student Jim Morrison, who would later rise to fame as lead singer of the seminal Los Angeles-based rock band, The Doors.

The Archive was recently in touch with Alexander Prisadsky, director of Five Situations for Camera, Recorder and People, and asked him to share his recollections of the making of his student film, and his collaboration with classmate Jim Morrison. Mr. Prisadsky’s generous and insightful personal notes below provide a fascinating glimpse into the history of UCLA's famed film school in the 1960s, perfectly setting the stage for the Archive’s upcoming screening of these rare archival treasures.

By Alexander Prisadsky

My UCLA student film, Five Situations for Camera, Recorder and People, was shot on March 20, 1965, in a Saturday Workshop called “Theater Arts 170." There were only about seven students in the class and it was the first time most of us had ever worked with 16mm film. Terence McCartney-Filgate was the course advisor. Edgar Brokaw was supposed to be the advisor and we had signed up for his section, but he was ill that term. Brokaw was very encouraging of experimental work. He felt that every student should make at least one experimental film at UCLA. Filgate had made a documentary, The Back-breaking Leaf (1959) for the National Film Board of Canada, that was pretty well known. Colin Young recruited him, I think. Young was very interested in the cinéma-vérité movement. He also brought in James Blue, who was very influential at UCLA, and Claude Jutra. He co-sponsored the ethnographic film program (of which I was a part).

For the first half of the term, the class met and developed scripts. Then each Saturday one student would direct, and the others would serve as production crew. Projects were 16mm, non-sync. We used a Bell and Howell Filmo, essentially a WW2 wind up combat camera, and were issued a Uher reel-to-reel portable tape recorder for non-sync sound, and a few hundred feet of film. The usual routine was to shoot the picture for a given scene, and then repeat the scene for the sound recordist. I had developed a script about a man who missed his bus and thus was forced to notice what was going on around him while he waited for the next one. I wasn’t happy with it.

Jim Morrison shot, I think, the week before I did. Mostly, he shot on his own outside the class, but used us (his crew) for a scene in which the conceit was that we were all watching a stag film when it broke. When it failed to resume, we started making noise, increasingly louder, making shadow puppets on the screen. Jim had us do quite a few takes, especially for sound. The result was that we got literally high from the repeated shouting. I was still high from it later that evening, couldn’t concentrate on anything, so I went out to a movie. I ran into Ran Erde, a student from Israel who was to be my cameraman. He was there for the same reason: high from the experience.

I lay down on my bed, closed my eyes, and tried to imagine what I wanted to see on the screen. I wanted to do something with crowds, to carry farther the stimulation Jim had unleashed with his scene.

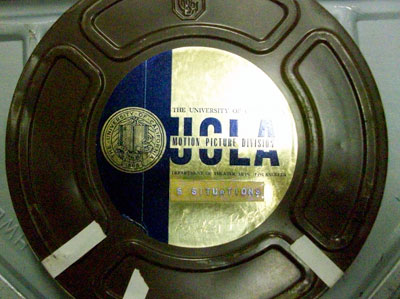

During the next week, I became increasingly unhappy with my script. Didn’t think it would work. So I lay down on my bed, closed my eyes, and tried to imagine what I wanted to see on the screen. I wanted to do something with crowds, to carry farther the stimulation Jim had unleashed with his scene. The new script became an unstructured series of scenes that I wanted to see on the screen. It was such a departure for me that I thought of calling it A Piece of Shit, so that if it was called that, I could just say, “yes, that’s what it is.” I didn’t though. Instead, I came up with the working title, Why Not? Only later, in editing, did I decide to call it Five Situations for Camera, Recorder and People. I wanted a title that said nothing about the content or emotions, but described the form. The structure also came later, in the editing.

The week before I shot my film, the UCLA basketball team had won games in "March Madness." After each win, a crowd of students from the co-op dorm I was living in and nearby fraternities formed in the street (Landfair), building a bonfire in the middle. Since my new script was going to be about crowds, I arranged to have a camera Friday night the 19th, looking for maybe a single good shot of smoke rising, lit from the rear by the fire. Instead it turned into a whole sequence. So I shot some more Saturday night after I sent the crew home. In the editing, the fire sequence became the focus of the film.

Before the shooting of Five Situations, I asked all my crew, along with my friends who were in it, to wear dark suits. Morrison was the only one on the crew who didn’t have one, which was one of the reasons I asked him to be the sound man. The other was that I had seen he had a feeling for sound. He had used some outtakes from someone else’s film, some aerial shots I think, and placed various sounds over them: some Bach, and then some thunder. Each transformed the image into something new and mysterious. After another student’s audio mix session, Jim once said, “Maybe I should be in radio instead of film.”

During my film’s bathroom sequence, Jim insisted on getting into the crowd and jostling around with them while holding the mic. This produced a distorted, concussive sound which I liked, but that I later slowed down to emphasize the violence of it even more. During the film’s final marching scene, I needed someone to call cadence for the audio. I found one of my crew who did it well, but if I had known of Jim’s military background and vocal abilities, I probably would have asked him to do it.

There was another scene I had written for the film, to take place on the long steps of an old, large church, with the men in suits. But by the time we finished the other scenes, it was about 5 p.m. We were all tired, and I knew I would be shooting more of the fire scene that night if UCLA won their game. So, I called it a “wrap.” Fellow student Ron Raley said he was disappointed because the scene seemed like it was going to be fun.

Edgar Brokaw had taught us all in editing class to “double splice” our workprints before turning them in to be projected at the end of the term. Edits were made with a transparent adhesive tape. The single sided splices would go fine through the editing machines but tended to buckle in a projector. I remember sitting in an editing room making my splices double when Jim walked by. He asked me what I was doing. When I told him, he just brushed it off, clearly having no intention of doing it for his film. During the term-end screening in the Warren Hamilton Theater, one of Jim’s splices buckled, caught in the projector, ending the screening of his film. He took a lot of heat for that, especially from Edgar Brokaw, a stickler for craft, with a short fuse, who, ironically, was probably the faculty member who most respected Jim’s ability and imagination.

Author’s note: Please keep in mind, this oral history is all to the best of my memory. It has been a long time. I wouldn’t be surprised if some of my recollections conflict with the memories of others. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY AUTHOR.

Celebrating Orphan Films series on May 13 and 14, 2011, will also include:

- A screening of the 1960s-era UCLA student film Patient 411. Director Ronald Raley will introduce and discuss the film’s cinematography by famous UCLA film major, Jim Morrison of the Doors.

- A screening of Kinky, directed by James Joannides and Maurice Bar-David. This UCLA student film captures a psychedelic montage of students in front of Canter's Deli on Fairfax Avenue. Set to music by The Kinks. Presented by James Joannides, UCLA film school alumn.

For more information, and to purchase a $10 pass for all screenings, please go to "Celebrating Orphan Films".